A Q&A with How We Go Home editor Sara SinclairWe’re excited to share an inside look into one of the newest oral history projects from Voice of Witness: How We Go Home.

How We Go Home will illuminate the experiences of Native peoples living on reservations in the U.S. and Canada. Narrators will describe the impacts of forced assimilation, displacement, and the human rights violations emerging from institutional problems within the reservation system, while revealing Native society’s incredible capacity for resistance, healing, and survival.

How We Go Home is one of six projects Voice of Witness is currently incubating through the VOW Story Lab, which provides oral history training, editorial guidance, and project funding to human rights storytellers in need of institutional support.

We hope you enjoy the interview below with editor Sara Sinclair.

About the editor: Sara Sinclair is an oral historian of Cree-Ojibway, German Jewish, and British descent, and a graduate of Columbia University’s Oral History Master of Arts program.

About the editor: Sara Sinclair is an oral historian of Cree-Ojibway, German Jewish, and British descent, and a graduate of Columbia University’s Oral History Master of Arts program.

How did you become invested in Native American issues?

It’s a part of me. My grandfather Elmer, who is Cree-Ojibwa, grew up on the banks of the Red River in Manitoba, and as is so, so common for people of that generation in both Canada and the United States, he was taken from his family as a boy and forcibly sent to one of the many residential schools in Canada, or what are called boarding schools in the United States. It’s not something that he talked about a lot. But the legacy of the school was always very clear to me in looking at my family, the family that he created with his wife, and the experience that my father had as a child. That’s just a part of our family history.

My interviews began as a series of life history interviews with Native North Americans from Reservation communities who left to attend elite academic institutions and then returned home to work for their respective Nations. I was especially interested in how cultural assimilation is tied to abandonment of communal ownership of land; I wanted to make explicit this specific tension around leaving land (home) for school.

Can you say more about this tension between land and going away to school?

People discuss education as an assimilationist policy, and focus on cultural assimilation. Actually, it’s about much more than that. It’s also about changing the way that people relate to land. In order to move Native people who have a different economic system off of the land, the American and Canadian governments work to align the younger generation’s way of thinking with their own.

And so I was interested in how there’s that very negative element to the historical educational project, but at the same time, most of the people who I know who’ve attended these institutions found real value in education itself as a tool. It’s so common to hear about residential school survivors forcing their grandchildren to read. You know, “You’re going to read every night. I don’t care what you read, but this house is going to be full of books. I’m taking you to the library.” And so I was interested in exploring that conflict.

Can you tell us about one compelling moment that you’ve shared with a narrator?

I’ll never forget the drive around my narrator Ashley Hemmers’ reservation in Ft. Mojave. We stopped to see the new playground at The Arizona Village, a housing development where a lot of the tribe’s young families live. Ashley was a grant-writer at the time, and the playground was one of the first community development projects that she worked to fund when she moved home after school.

We parked the car beside the gate, opened it, and entered. Although Ashley lamented the lack of upkeep, the park, just a few years old, still looked good: bright and inviting. It was a Saturday afternoon in the desert spring and there was not a single person there. I rested in a swing for a few minutes. Ashley sat close by, on a bench in the shade. A couple of girls who had been sitting in a yard across the street picked up their basketball and made their way to the park’s court. They started to play.

A few minutes later we returned to the car. As I was closing the car door, I noticed that the girls were leaving too.

A few minutes later we returned to the car. As I was closing the car door, I noticed that the girls were leaving too.

“I wouldn’t say the area is unsafe,” Ashley said. “But if something happened to them here, it’s possible no one would see it. No one would be accountable.”

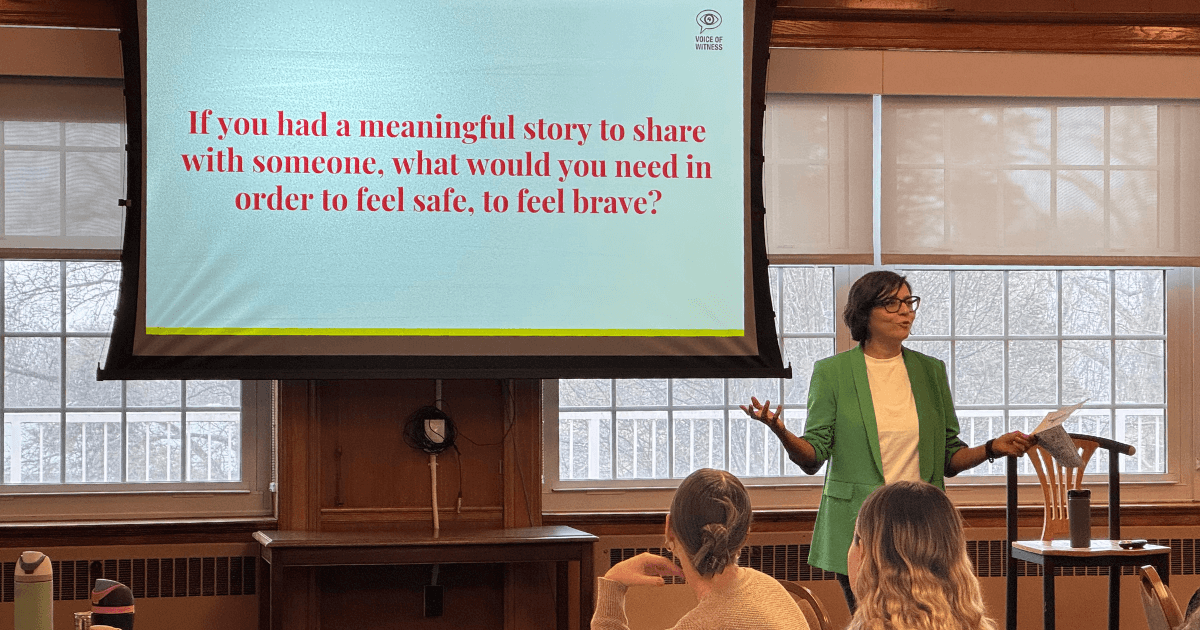

This moment is really etched in my mind; to me it illustrated the complexity of Ashley’s work. She’s done this amazing thing and created this space, but there’s so much more work that has to be done in order for this space to be fulfilled. These girls needed to know that there was a woman present in order to feel safe, in order to come out and be a child and play. You can’t just create a beautiful space. It also has to feel safe to be there.

And that’s her continuing work, to work with her community to heal together from the impact of generations of assimilationist efforts and U.S. policies that have taken an enormous toll on Native American and Canadian families.

What are some of the challenges that come with this project?

For many reasons, reservation communities in particular tend to be pretty far away from where most other North Americans live, and so it does require a lot of travel. I traveled to South Dakota in the spring of last year, and it was three flights to get to where I wanted to go, and then a long drive through this flat wide prairie land. You really feel the size and the shape of the continent.

But the travel is really important, because the kind of intimacy that’s required for these conversations is not something that I can achieve over the phone. It’s just not. I want people to feel these stories. I don’t want these words to be flat. You know so much more what to ask when you see somebody in their own environment.

Where are you now in the project? What would support allow you to do this summer/fall?

I’ve completed about a third of the interviewing on the project. I hope to receive support that will allow me to return to Ft. Mojave and Rosebud, South Dakota and to travel to conduct new interviews with communities in Winnipeg and British Columbia, Canada.

What hopes do you have for the project?

I hope that it offers people a different way of knowing about and thinking about the Native American experience. I don’t think that there’s a lot of opportunity to hear directly from Native North Americans about their experience, and definitely not in a way that’s framed historically. Sometimes I talk to people about what I’m doing, and people are very honest. They say, “Why are there these problems in Native American communities? Why are there these challenges?”

I think people don’t think about the impact of history on contemporary lives, and so I hope that this book can be an answer to some of those questions.

Click to help Sara amplify Native voices.

Make a Gift Today