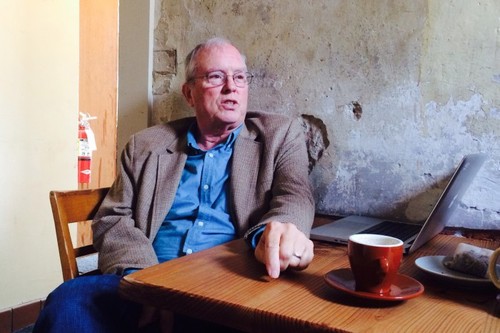

By Rick Ayers

Rick Ayers is an assistant professor of education at the University of San Francisco in the Urban Education and Social Justice cohort and a member of the Voice of Witness Education Advisory Board. Rick taught in the Communication Arts and Sciences small school at Berkeley High School, where he pioneered innovative and effective strategies for academic and social success for a diverse range of students. He is the co-author, with his brother William Ayers, of Teaching the Taboo: Courage and Imagination in the Classroom and is also author of A Death in the Family: Teaching through Tears. You can contact him at rjayers@usfca.edu.

A Worthy Project

Recently, a group of students from a progressive private school on the north side of Cleveland undertook to understand the history of the school’s immediate neighborhood. The commercial district had transformed in the way typical of modern cities: the old hardware store where you could pick up a screw for a penny was now a hipster cappuccino joint; the Polish bakery had become a music store that was itself retro, selling old vinyl discs.

Under the leadership of a dynamic and thoughtful history teacher, they set out to uncover the local stories, to do history instead of merely studying history – they were developing and analyzing their own primary sources. If the neighborhood was becoming hipster now, this was only the most recent change; before that it had been mostly Puerto Rican, before that African American, before that Polish, and before that Italian. Layers upon layers could be sifted from cultural artifacts and leftover residents from each period.

And it was a worthy project – a rich site for oral history. Students explored the neighborhood, gained the trust of residents, and conducted interviews that illuminated many aspects of the neighborhood and uncovered hidden truths. For these students, it was an exciting experience. They created video reports, web sites, and even a book on their research.

But. Do you see a problem here? Is something missing from the lesson taught? I think there is. And it is a common problem in the social studies – in history, sociology, anthropology, even education.

The issue, as is so often the case, is power.

Who Benefits?

Who got something out of this project? Who took and who gave? What are the consequences of this encounter for the students and for the low-income community residents? Clearly the students got something: they got their A’s in history, completed high school, and went on to interesting college careers. The residents? Perhaps they were allowed to see the web site; they might have been to a public exhibition of the oral history project and received applause. But two years hence the students are in college and the residents are still there – or perhaps evicted to make way for condominiums.

I experienced something similar when the high school where I taught became the focus for a deep, six-year study from UC Berkeley called the Diversity Project. As many as 24 graduate students, led by a few inspiring faculty members, descended on the school and studied everything – from class choice to social clubs to discipline policies. The results were a stunning expose of de facto segregation and tracking. We teachers had high hopes that the volumes of data uncovered would create an irresistible pressure for change, would make the school better.

In the end, though, the administration gritted its teeth and voiced some mea culpas; the researchers were thanked for their good work and sent back up the hill; and the school continued in its inequitable default mode. The teachers who helped with the study certainly appreciated the attention and the chance to uncover the workings of the school. But two years later we looked around and there were 24 grad students who had received their PhD’s and gone on to prestigious academic careers; and the high school was stuck pretty much in the same place. The grad students had studied our problems, they had measured and probed and questioned and theorized. But they had not helped.

Embedded Power Dynamics

This problem of power is embedded in the very character of social research. Some people are the objects of the research, some are the subjects who define and explain the reality. Traditional western anthropology sees its own culture as proper and objective, while those studied are interesting, sometimes exotic. The framing of some people as civilized and advanced and others as savage and backward happens not just in world politics but in our own neighborhoods. This is seen in the contrasting terms like developed vs. underdeveloped (or developing), religion vs. myth, rational vs. impulsive, Proper English vs. slang, and gifted vs. at-risk. Even the prerogative to name what one sees, the power to describe and categorize and theorize about a studied culture, is itself an act of colonizing, of subordinating.

In oral history, we celebrate the voices of those often silenced, we ask the interviewees to tell their own stories. Oral history is radical because it seeks to reverse the traditional narrative voice of history, to look from the eyes of the oppressed. This is all good, but even here we must be careful. Because, as with documentary film, we still exercise great power in our ways of framing stories: in the voices chosen, in the introduction given, and most importantly in the editing of the transcript.

Students should absolutely do oral history and research projects in their own neighborhoods or anywhere. But history is not just another conversation – it’s an ongoing negotiation of meaning and action. As Gayatri Spivak has said, do the subaltern get a right to speak or does someone else always presume to speak for them? Students should trouble their thinking about voice, perspective, and agency. Students should be excited by what they learn, but, as important, they should be humbled. They should ask themselves: Who gets to define the question at hand? Who gets something out of this encounter? What action does the project demand of us?

In this way our work is not just a matter of taking – it can become transcendent, a genuine and participatory engagement with the world.

That is the best education.