by William Ayers

William Ayers is a member of the Voice of Witness Educational Advisory Board. He is a former Distinguished Professor of Education and Senior University Scholar at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC), the founder of both the Small Schools Workshop and the Center for Youth and Society, and he has written extensively about social justice, democracy and education, the cultural contexts of schooling, and teaching as an essentially intellectual, ethical, and political enterprise.

We are all refugees from our childhoods. And so we turn, among other things, to stories. To write a story, to read a story, is to be a refugee from the state of refugees. Writers and readers seek a solution to the problem that time passes, that those who have gone are gone and those who will go, which is to say every one of us, will go. For there was a moment when anything was possible. And there will be a moment when nothing is possible. But in between we can create.

—Moshin Hamid, How to get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia

I shall create!/ If not a note, a hole/ If not an overture, a desecration.

—Gwendolyn Brooks, “Boy Breaking Glass”

After a long period of illness and suicidal despair, the tormented French painter Paul Gauguin created a vast and sprawling panorama that suggests a wildly improbable Garden of Eden, or perhaps an outrageous tropical island with a looming mountain surrounded by water, twisted orchards, a large blue idol with a peaceful expression and uplifted hands, cats, a dog and a contented goat, as well as a man in the center plucking fruit, a baby, a young child, several grown women, and a withered hag. Gauguin scrawled the title of the work on its surface, which reads in English:

Where do we come from?

What are we?

Where are we going?

These questions were troubling, even horrifying for Gauguin, but for us—teachers and students, writers and readers—they may prove to be a useful provocation and a powerful invitation toward other important questions.

How do you see yourself and your problems/challenges/potential? What have you learned from your experiences and your journey thus far? In other words, what’s your story?

All human beings lead storied lives, of course, spinning our tales to ourselves, to family and friends, and sometimes out into the wider world, sampling and collaging and curating shards of reality, and weaving them into intricate webs of meaning that make our lives significant and tolerable. We invent a past, we imagine a future, and here we are: suspended in the messy muddy middle.

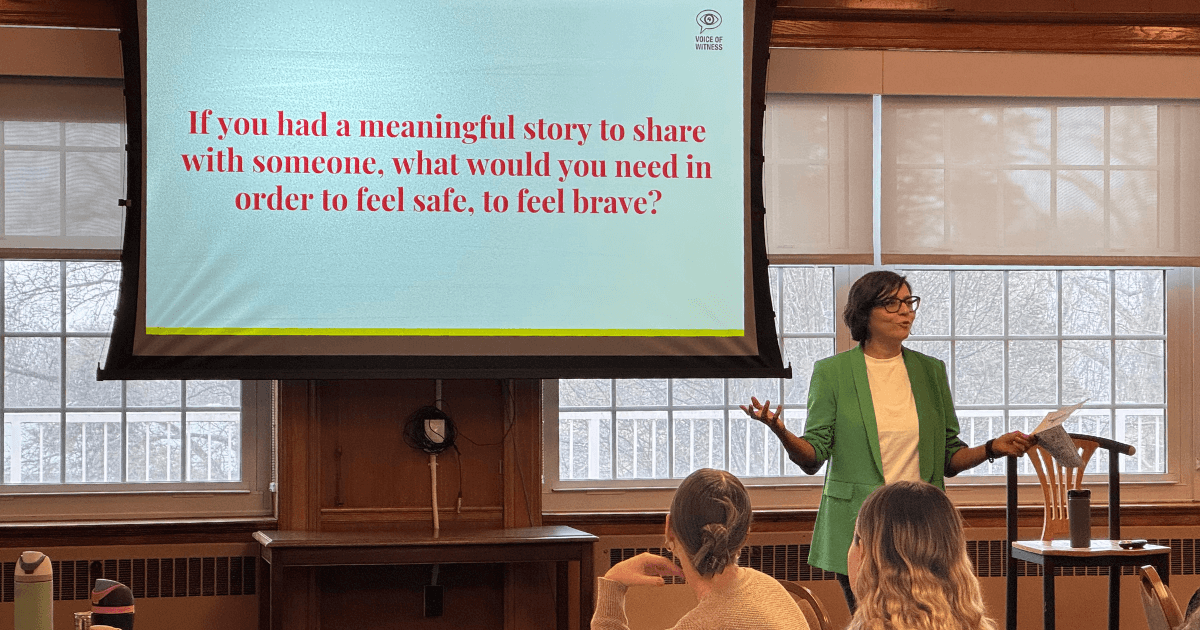

Oral history adds to the depth and reach of democracy when it asks people to make sense of their experiences and their lives: “What’s your story?” The question rests on an assumption of agency, a belief that all human beings make meaning no matter what, that each of us is free and fated, both fated and free. And we are never so free as when we are naming our situations and resisting our fates, storming the heavens and telling what it’s like for us.

There is never a single story to tell—there are hundreds, thousands, millions of stories, each one embedded in a cascading cacophony of convergent and divergent stories. Every day another story and every person a philosopher, an expert on his or her lived experience. Oral history relies on the people Studs Terkel called, “the etceteras of the world,” the extraordinary ordinary people who speak in the “poetry of the everyday.”

All human life, of course, is in part a story of suffering, loss, and pain. When that pain is preventable, the suffering undeserved, the loss avoidable, we resist, and in that opposition we find another common-place in our human story: refusal, resistance, revolution. Sometimes our stories are ignored or diminished by others, sometimes we are seen through the heavy lenses of stereotype and label, our undeniable and indispensable three-dimensionality suffocated and diminished, our hopes handcuffed and our possibilities flattened and policed. The development of a more powerful and compelling voice becomes even more essential.

Telling our stories, trusting our stories, listening carefully and empathically to the stories of others, revising and editing, starting over, creating a new draft is part of the vocation of oral history and the indispensable work of democracy. This is because democracy is based on a fragile but precious ideal: every human being is of infinite and incalculable value, each an intellectual, emotional, physical, spiritual, signifying, and creative universe swirling through the vortex of time and space, dancing the dialectic with a zillion other universes, and that everyone counts and nobody counts more than anyone else. In a true democracy the fullest development of each becomes the necessary condition for the full development of all, and conversely, the fullest development of all is the condition for the full development of each.

“Who built the pyramids?” Bertolt Brecht asks to kick-start his poem, “A Worker Reads History.” It’s a provocative question, for while the pharaohs may have wanted to aggrandize themselves and persuade future generations that they had been powerful and splendid gods—they may have longed for immortality—they certainly did not build the pyramids: Did their backs bend to the task, or their hands crack? Were their bodies broken? Clearly the peasants and the slaves did the actual work; it was they who hauled the stones and mixed the mortar. But since no one ever went among the builders and asked them what it was like, how they did what they did, how they got those massive stone blocks arranged just so, and what it all meant to them, a colossal piece of history was lost.

Bertolt Brecht re-imagined history from the angle of the worker:

When the Chinese wall was built

Where did the masons go for lunch?

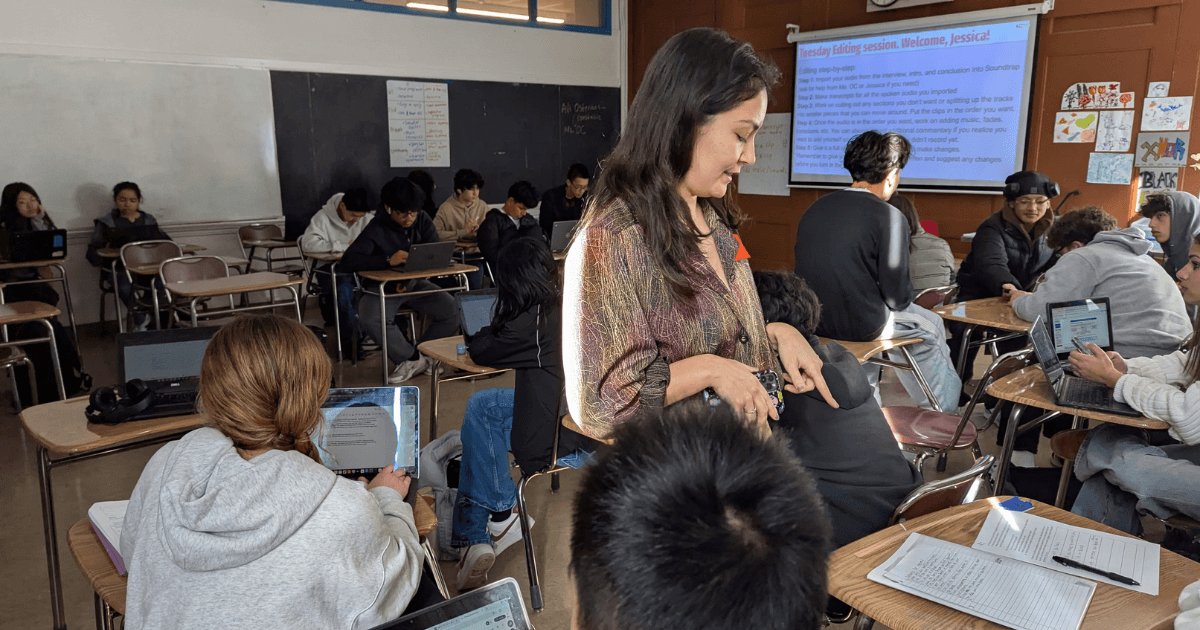

Central to an education for citizenship, participation, engagement, and democracy—an education toward freedom—is developing in students and teachers alike the ability to think and speak for themselves, to tell their own stories and to seek their own truths. The core curriculum—explicit or assumed—of a liberating education is this: we each have a mind of our own; we are all works-in-progress swimming toward an uncertain and indeterminate shore; we need no one’s permission to interrogate the universe, or to act on what the known demands of us; we can each tell our own story.

People can contribute to making the world a more humane, peaceful, democratic, just and joyful place when we have the opportunity to come together as communities of equals to share stories from our lives, to draw on those stories to examine and reconsider the conditions of our existence, to resist being objectified or thingified as we step into history as actors and subjects exercising our stubborn agency, and to learn to accept the fact that we are human.

What’s your story? How is your story like or unlike other stories? Where are the common edges, and where do our stories veer off into unique and distinctive highways and alleys? What’s next? What are the next chapters going to be and the chapters after that, and after that?