2019 marks 10 years for Voice of Witness as a nonprofit, and in celebration of this exciting milestone, we’re resurfacing powerful stories from every oral history book in our series. Though time has passed since these stories were first published, many of the themes and issues they address are as relevant and important as ever.

For nearly five decades, Colombia has been embroiled in internal armed conflict among guerrilla groups, paramilitary militias, and the country’s own military. Civilians in Colombia face a range of abuses from all sides, including killings, disappearances and rape—and more than four million have been forced to flee their homes.

For nearly five decades, Colombia has been embroiled in internal armed conflict among guerrilla groups, paramilitary militias, and the country’s own military. Civilians in Colombia face a range of abuses from all sides, including killings, disappearances and rape—and more than four million have been forced to flee their homes.

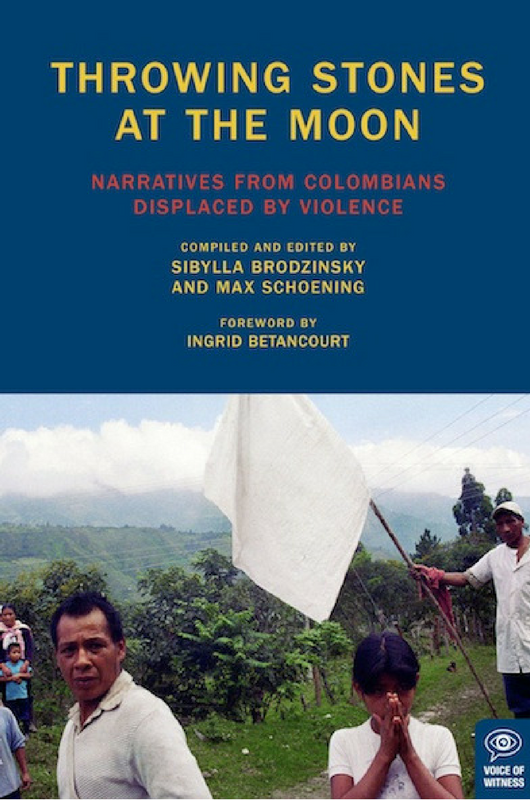

The oral histories in Throwing Stones at the Moon describe the most widespread of Colombia’s human rights crises: forced displacement. Speakers recount life before displacement, the reasons for their flight, and their struggle to rebuild their lives.

As you read the book, check out Displaced in Colombia, a multimedia project that brings together oral history and documentary photography to explore contemporary first-person stories of people impacted by the decades-long violence in Colombia, and our accompanying education toolkit, designed to engage students with the human stories behind the headlines, and provide a model for photographers and journalists exploring interdisciplinary approaches to human rights reporting.ORDER THE BOOKDOWNLOAD THE TOOLKITDANNY CUERVO’S STORY

Danny Cuervo arrived in Ecuador in 2004 after fleeing from one of the right-wing paramilitaries’ biggest training camps in the Eastern Plains of Colombia. He had gone there half-willingly when he was nineteen, lured by the promise of money to support his soon-to-be-born son. He immediately realized it was a mistake, and managed to escape. Fearing the paramilitaries would track him down and kill him, he fled to Ecuador. At the time of his interview, he described the struggles he faced trying to raise two small boys as a single father, while fighting the discrimination and exclusion that many Colombian refugees suffer in Ecuador.  ARE YOU COLOMBIAN? SORRY

ARE YOU COLOMBIAN? SORRY

I’ve been raising my children alone here since María went back to Colombia. One is five years old and the other is three. It’s hard.

Ecuadorans humiliate you here every day. I’ve tried to find steady work many times. I’ve looked in supermarkets, in a rotisserie chicken restaurant, in the market, but people say, “You’re Colombian? No.” Many times I’ve also tried to find another room to rent, something a little larger, and I get the response, “Are you Colombian? Sorry, sorry.”

“I had given the children breakfast, but there wasn’t enough for me, so I’d left our room hungry.”

I’ve had a lot of problems with Ecuadorans. One day I was working on a bus from here to Otavalo. That morning, I had given the children breakfast, but there wasn’t enough for me, so I’d left our room hungry. Then I’d gone out to make enough money to buy something for our lunch. I got on a bus and I started to go around selling some necklaces made of stone, and I gave my talk:My name is Danny. I’m not from here, I’m from the neighboring country of Colombia. But thank God I’ve been a refugee for more than three years, naturalized in this beautiful country, which has given me beautiful opportunities.

I’m an artisan; I didn’t come empty-handed. I’ve made this beautiful necklace. It’s made out of nylon and stone. I won’t be the one who puts a price on it. If you think that my creativity could be worth $1 or $1.50, I’ll take it, whatever the necklace is worth for each person.

I’m also going to do something nice for those people who don’t have money. I’m going to give one as a gift, but with a commitment. The commitment isn’t with me, but with your conscience, your heart. If tomorrow you find a kid or an elderly person on the street, don’t discriminate against him for the condition that he’s in. Rather, give him something. Maybe it seems strange to you and you’ll ask why I say that. I do it and say it because I believe in the law of compensation. That beautiful law that has taught me that if today we act correctly toward other living beings, tomorrow we won’t lack anything. I won’t inconvenience you anymore. Maybe you’ll like this beautiful art and you’ll want to buy it.

But I didn’t sell anything. I got on another bus going to Atuntaqui, but I didn’t sell anything there, either. From Atuntaqui back to Otavalo I sold nothing. On the bus from Otavalo back to Ibarra, I was desperate, extremely desperate.

I began to hand out the necklaces to the passengers, saying, “Excuse me, sorry. Look for just one minute, check out the craftsmanship.” I got to a gentleman in a suit, with glasses, apparently well educated, and I said, “Excuse me please, check out the necklaces.” I used the informal “tú” form to address him. He said, “Don’t use ‘tú’ with me. What balls! What am I to you that you treat me that way?” Everyone stopped to look at me. I said, “Okay, have some respect. I’m working here, I won’t bother you again. If you don’t want to look at a necklace, that’s fine.” This time I used the formal “usted” form to address him. He called me “abusive and rude.”

I could hear: “Colombians play the fools, but they get on the bus to steal. Just let your guard down and see that he’ll rob you.”

After handing out the rest of the necklaces I started giving my regular speech about the law of compensation—that if we act correctly today, tomorrow things will go right for us. I kept talking, but in the back, almost in the last seat, I could hear: “Colombians play the fools, but they get on the bus to steal. Just let your guard down and see that he’ll rob you.”It was hurtful and I thought, I have to say something to let out my anger. I went toward the back of the bus, and I said, “You know what, shut your mouth, unless you want me to hit you!” Just then all the passengers stood up. At first I thought it was to defend me but then I saw that they were against me. “Shut up and have some respect,” they told me. “You’re not in your country. If you have work and eat it is thanks to our country. You come here to take the jobs of Ecuadorans.”

A man pushed me and said, “Have some respect brother.” I couldn’t take it anymore. I took the necklaces and pa! I hit him in the face. And because they were made of stone, they broke his nose.

The other passengers grabbed me and called the police. It was horrible; I had gone out to make enough money to buy food for lunch and I ended up being locked up. I called home and asked the daughter of my landlord, who took care of my children when I went out, to watch over them. I spent five days in jail for making a public scandal.

From that, I learned that no matter how much I get humiliated, no matter what people say to me, no matter if I get beaten, I have to stay poker-faced. Maybe it’s not what I want, but I have to do that. I have to take it, I have to swallow my pride, my anger, my pain, because if I say something, I may get locked up.