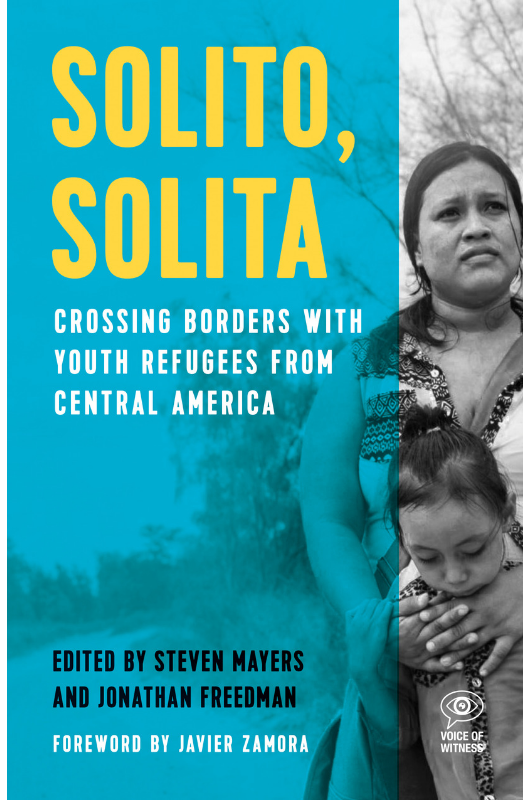

By Steven Mayers and Jonathan Freedman

When we began interviewing youth refugees from Central America four and a half years ago, we never imagined that a caravan of Honduran refugees would arrive in Tijuana the same day that we would present our book, Solito, Solita, to a Binational Conference on Border Issues. The convergence of real-time events and narrators from the book bearing witness to why they fled poverty, violence and abuse as children revealed the potentially transformative power of Voice of Witness to challenge stereotypes and affect change – if only we listen.

The dominant narrative portrayed by the White House is that armed and dangerous illegal immigrants are invading the United States and must be stopped by a Great Wall, running along the 2,000-mile border, defended by Border Patrol and backed by thousands of US troops. The fifteen humble, heart-wrenching and often heroic autobiographical narratives in our collection are each unique, yet together they follow a pattern: Children abandoned, abused, and hungry have little choice but to flee for their lives; they endure incredible hardships on the journey, seeking refuge and reunion with their parents in the United States.

For Soledad and Gabriel, two of the narrators in Solito, Solita, it is emotional and cathartic to cross the US-Mexico border again, this time traveling south with passports.

On Thursday, we present our panel at San Diego City College to a full room of forty people. The audience is mostly college students as well as some professors from City College and El Colegio de la Frontera Norte in Tijuana. Many in the audience are in tears as Soledad and Gabriel recount stories about their childhoods in Honduras surviving poverty, sexual abuse, and threats from maras, gangs.

Citing a professor from Mexico City, Professor Enrique Davalos of San Diego City College says, “This is no longer a caravan. It’s an exodus. We are in support of organized communities struggling to escape cycles of poverty, violence and opportunities.”

We walk across the border on Thursday evening as the sun turns the sky blood red. Soledad and Gabriel feel uneasy as we cross a walkway lined with concertina wire towards Mexican customs officials. This is the first time Soledad and Gabriel have walked across the border since their crossing as teenagers. Although they are heading south this time with documentation, the walls, wires, and the steely faces of the border patrol bring them back to the places of their trauma.

Friday morning, we visit Playas de Tijuana under bright sunny skies. We are at the extreme, northwest border of Mexico with the United States. A brightly colored monument states, “Tijuana, la patria begins here.” We tend to think of Tijuana as the end of Mexico, but from Tijuana’s perspective it’s the future. Gabriel says, “I like the message, ‘here begins the country.’ It’s not sad, but happy – a beginning.”

The Mexican side of the border fence is virtually empty. The only signs of the geopolitical drama are two workers in orange hardhats stringing fifty meters of razor wire above the vertical steel bars of the fence driven into the sand. The fence descends from a ridge to the lapping waves of the Pacific. The border, like the sea, is peaceful. On the California sands half a dozen people are riding horses. Every few minutes a US military or Border Patrol helicopter chops the silence, reverberating on the fence bars like tuning forks amplifying a surreal virtual reality of imminent invasion.

Five thousand US troops in full combat gear are bivouacked on the US side of the border a few miles east, out of sight. They were dispatched as a show of force by President Trump to stop what he called, in a Tweet, an “assault on our country by Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador…” Or, as some retired military officers object, was this a political gambit to sway the midterm election?Soledad and Gabriel warily eye the fence, the symbol of so much fear, enmity, and political outrage from the White House. “Is that America over there?” Soledad points at the sandy beach where people ride on horses forty yards away “It’s so close.” You can see the shimmering towers of the Hotel del Coronado, where L. Frank Baum conceived of the Emerald City of Oz. A drone hovers above us, its camera eye blinking. Anger wells up from our chests. Where is the army of migrants invading the US? Is this a national security threat?

Trump’s narrative about dangerous criminals storming the border only makes sense from very precise camera angles.

A half-dozen refugees from Honduras carrying backpacks stare in a daze of exhaustion, hunger and anxiety. Gabriel says he feels “a sad impotence not being able to do anything. It looks like they haven’t slept for a long time. They are hoping they can find a shelter with mattresses that they can sleep on. They’ve been begging in the streets.” Tijuana police load them on the back of a pickup and bump over a ridge to a stadium.We hear from a young Honduran refugee staying at the small Border Angels shelter in Las Playas that there had been a thousand or so refugees at the beach two days earlier. Some Tijuananas, including members of the Border Angels and other organizations, hand out food, jackets, and supplies while the tired travelers rest on the beach at the foot of the border fence. Some wealthy residents approach the migrants with signed letters that inform them that they are not welcome on what they argue is their beach because they own property in the area. When tensions rise, the property owners begin to yell insulting and racist slurs at the defenseless refugees, calling them “invaders,” just as Trump has. Our Honduran friend tells us that since this incident, the police are transporting migrants who arrive at the beach to shelters as well as to a nearby baseball field.

Looking through the metal bars of the border fence at the newly installed concertina wire and the border patrol officers, Soledad reflects:

I crossed the border when I was fourteen years old in Texas. Coming across the border from California into Tijuana years later now, I have the same feeling, the same feeling that I had to jump the fence and ask for help. It is really traumatic for me to see the border again, and to see how the people there are so close to their dreams and they can’t make it. And I feel really sad and emotional, and at the same time mad. Why do we have to have to have the border to be by us?As a person coming from Honduras, I know all of the challenges that we go through over there, not having the support from the United States. Instead of helping us, they are putting up a lot of fences and just crushing out our dreams to become someone better and to have a better life. While I am looking across the border I am thinking: Wow, it’s just one step forward and I could change my life. All these people could change their lives if those fences weren’t there. It is so sad that we, humanity, are dividing? It is a mix of emotions. I now have the power to help. I see myself when was fourteen years old, jumping the fence, asking for help. I was tired. I can remember everything now. That was over ten years ago and now those memories are so fresh. Someone was helping me across the border. I had been given drugs because I was so tired, and I couldn’t keep walking. A lot of those memories came back. Just to be in front of that border, thinking about all of those things I went through.

We reach Campo Benito Juarez, the baseball stadium, about two miles east of Las Playa, just south of the border. Families with young children sling makeshift tarps to block the sun and sleep in the shade. Their shoes are worn, bare feet dusty, blistered. Coughing. The grippe.

A Honduran mother and her ten-year-old son have trekked for a month from Copán, near the ancient Mayan ruins:

Life is un poco difficult for a widow with two children,” she says. “There is no work, but much hunger. My motive to join the caravan was the death of my husband, on December 18 a year ago. He had diabetes and died at thirty-four. He was a master of many trades, electrician, welder, ceiling installer, mechanic. I worked in a tobacco factory, grading the tobacco. But it was piecework. I couldn’t feed my two children. The moment I heard that the caravan was passing through the town of Santa Rosa, I took my son and left. My two year old was too frail for the arduous journey. I left my little girl with my mother and grandmother. There were about 2,500 people. So many women with tender little children. Each day, we’d start walking at five am, and break off at three in the afternoon. When we crossed the bridge at Tecún Umán, Mexican federales fired tear gas. Two boys died of asphyxiation.

Were there any gratifying experiences on the caravan? Her eyes begin to tear. “Not a single happy memory on the caravan.” What are your next steps?

I’ve got to achieve my objective! How am I going to enter the United States? Our leaders are with a caravan of people who fell behind. They are sick of grippe, coughing, foot injures. We came always dreaming! We’re waiting for the decisions of our leaders. My dream is to work hard for my two children. I have faith,” she points to the sky, “that I will be able to enter. My second dream is to bring my little girl. To the American people, I plea that you give us opportunity.

A Tijuana volunteer brings a dozen knit caps. “Does anyone want a hat?” “May I have one for my son and for myself?” She takes them gratefully. “It’s cold at night.”

A San Diego bakery van drives up. The driver flings open the rear doors. “Bread!” Instantly, dozens of refugees rush to the back of the van, where the famished refugees come away with a bun. Another volunteer dispenses bottles of water from his trunk. There is not enough bread and water to go around. About seventy-five refugees, mostly young men wearing tattered t-shirts, move around in a confused mass. Mexican police in military gear and armed with machine guns watch warily from the sidelines. Suddenly, we hear shouts. Three migrants hustle through the crowd, carrying a man lying on a blanket used as a stretcher. A doctor pushes through. “Stand back, give him air.” The doctor resuscitates the man. A dozen minutes later an ambulance arrives and drives off siren waling. Dr. Allen Keller came to Tijuana from New York University, where he directs the Center for Survivors of Torture at Bellevue hospital.

A San Diego bakery van drives up. The driver flings open the rear doors. “Bread!” Instantly, dozens of refugees rush to the back of the van, where the famished refugees come away with a bun. Another volunteer dispenses bottles of water from his trunk. There is not enough bread and water to go around. About seventy-five refugees, mostly young men wearing tattered t-shirts, move around in a confused mass. Mexican police in military gear and armed with machine guns watch warily from the sidelines. Suddenly, we hear shouts. Three migrants hustle through the crowd, carrying a man lying on a blanket used as a stretcher. A doctor pushes through. “Stand back, give him air.” The doctor resuscitates the man. A dozen minutes later an ambulance arrives and drives off siren waling. Dr. Allen Keller came to Tijuana from New York University, where he directs the Center for Survivors of Torture at Bellevue hospital.

The migrants are frustrated, weary, and anxious. It’s tense.We meet a Mexico City-based reporter from Agence France Presse, camera crews from CNN and NBC. The video cameras are inactive until there’s the slightest commotion, where they rush up. Viewers see the chaos and pain and anger amplified by the presence of cameras. Inside the stadium, families are resting on blankets; a mother is crying inconsolably, her husband hugging her; aid workers are handing out supplies. Through the chain link fence, the encampment looks well organized and peaceful. But outside the stadium it’s chaotic, desperate young men seething with frustration at their powerlessness trapped between the stadium and the concrete containment wall.

Soledad reflects on meeting members of the caravan.

Seeing all of the children in the caravan and seeing how they’ve gone through the same challenges that I went through. It was really hard for me, and shocking as a person from Honduras. I know that sometimes we don’t have a choice: immigrating is not a choice, but a way to survive. If there were more opportunities for people in Honduras to survive, they would not be making this trip. I had to leave my family behind. Starting a new life is full of challenges: living alone, leaving your family. It was a really hard decision to make and all of those decisions that I made when I was fourteen years old. Crossing the border is painful. You’re leaving behind your sisters, your brothers, your friends, sometimes your parents, in my case. It is really hard for me to think about all of that at this moment.

On Friday afternoon, we present at La Universidad Autónomo de Baja California in Tijuana at six. A Tijuana college student in the audience raises her hand and says to Soledad: “Before hearing your story, I felt differently about the caravan. After listening to you, my mind has changed correctly. I support the caravan.”

Soledad has a message to share with people in the United States:

These are children that we are talking about, hundreds of children, thousands of young people. I’m pretty sure that there are a lot of moms out there. We all have families, and I‘m pretty sure that they are going to sympathize with this situation. I want to believe they will. Please help. Whatever you see in the news is not exactly the reality. You have to really go there to see their suffering. You have to really go there to see their faces, their anger, their tiredness, their desperation. The children look confused. They don’t know what is going on. Their moms look tired, exhausted. It’s just really hard for me to comprehend all of this at once. I have nieces. I have nephews. I can’t imagine them in this situation, walking for days without shoes, without eating, sleeping on the ground! It hurts so badly because they don’t deserve that. We have the power to help them. We have the power to advocate for these people. I wish I could do more. Just to speak up, to learn about what is going on in Honduras. Just to speak to other people, to open up their minds to this situation. That is something. Right now they are the ones going through this but tomorrow it could be you.

Steven Mayers and Jonathan Freedman are co-editors of our new book, Solito, Solita: Crossing Borders With Youth Refugees from Central America. In this collection of oral histories, powerful narrators describe why they fled their homes, what happened on their dangerous journeys through Mexico, how they crossed the border, and their ongoing struggles to survive in the United States.

Steven Mayers and Jonathan Freedman are co-editors of our new book, Solito, Solita: Crossing Borders With Youth Refugees from Central America. In this collection of oral histories, powerful narrators describe why they fled their homes, what happened on their dangerous journeys through Mexico, how they crossed the border, and their ongoing struggles to survive in the United States.