2019 marks 10 years for Voice of Witness as a nonprofit, and in celebration of this exciting milestone, we are resurfacing powerful stories from every oral history book in our series. Though time has passed since these stories were first published, many of the themes and issues they address are as relevant and important as ever.

2019 marks 10 years for Voice of Witness as a nonprofit, and in celebration of this exciting milestone, we are resurfacing powerful stories from every oral history book in our series. Though time has passed since these stories were first published, many of the themes and issues they address are as relevant and important as ever.

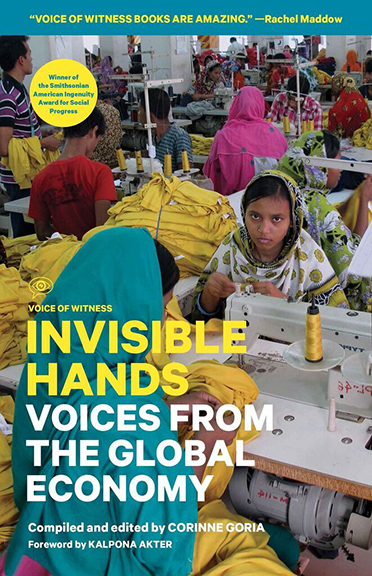

Invisible Hands: Voices From the Global Economy is an oral history collection that reveals the human rights abuses occurring behind the scenes of the global economy. The narrators—including phone manufacturers in China, copper miners in Zambia, garment workers in Bangladesh, and farmers around the world—share the secret history of the things we buy, including lives and communities devastated by low wages, environmental degradation, and political repression. Sweeping in scope and rich in detail, these stories capture the interconnectivity of all people struggling to support themselves and their families.DOWNLOAD CURRICULUM

Sanjay Verma’s Story

In December 1984, a pesticide plant in Bhopal, India, operated by the American company Union Carbide, began leaking the toxic gas methyl isocyanate, a chemical used in pesticides. The leak killed over two thousand Bhopal residents on first exposure. In the days and months afterward, thousands more perished from acute damage to their pulmonary and nervous systems. In all, nearly six hundred thousand were affected by the leak, with many developing lifelong chronic health problems. The Bhopal leak rivals the Chernobyl meltdown as the worst industrial accident in history.

Sanjay Verma was just an infant when the gas leak occurred, but the accident has shaped nearly every aspect of his life since. His parents and five of his seven siblings were killed that night. He grew up in an orphanage and then with his two remaining siblings, and he was inspired from an early age by his older brother Sunil’s activism related to the health and economic consequences of the gas leak. Not only have thousands of survivors suffered long term health consequences such as vision and respiratory problems, the groundwater in Bhopal has been found to contain other contaminants from the factory such as arsenic, mercury, organochlorides, and numerous other chemicals produced in the factory.

Sanjay talks about the family he’s lost to the disaster, his path to activism, and the ways the disaster continues to be felt in Bhopal:

In the 2000s, many of the people I met in Bhopal had health problems, especially the people who were in their thirties and forties and fifties. Most of them were suffering from breathlessness, and they got tired after walking for even five minutes. Before the disaster most of the people in town worked as laborers. THey would carry wheat, or they would sell vegetables on a handcart in the streets, or they would work as masons. They lost their working ability because they inhaled poisonous gases the night of the gas leak, and many are still easily fatigued and so cannot do hard work.

I didn’t have any effects from the disaster until 2005. That year, when I was twenty years old, I had a stroke. Half my body was paralyzed for about twenty minutes, and I was in an intensive care unit in the hospital for about three days. Then I had to go through some tests in a bigger hospital, and the doctors found out that my carotid artery had narrowed, and that’s what caused the stroke. I’m not sure why it happened, whether the stroke was because of the disaster or not, but there were a lot of hard- to-explain illnesses in town.

Not only were people still sick, they were still getting sick from drinking water that was contaminated from the disaster. Those of us who were active in the movement for victims’ rights worked hard to fix the problem.

I visited Delhi in march 2006 as part of a victims’ rights campaign organized by the International Campaign for Justice in Bhopal. Our city was still contaminated twenty years after the disaster, our drinking water was unsafe, and nobody had ever really been held accountable for the accident. We wanted to make Dow liable for contamination cleanup, since they had bought out Union Carbide in 2001. We thought they should compensate all the people who had drunk contaminated water for twenty years and also help clean up the site. We also wanted Warren Anderson to face trial.

Around seventy people from Bhopal went to Delhi to rally and demand to see the prime minister—we walked, even though it was over five hundred miles. It took us thirty-six days. The prime minister wasn’t willing to meet us, so a few of us went on a hunger strike. I was one of the fasters, along with seven or eight others. I fasted for six days. The prime minister didn’t come, but he called us, and then three or four of our representatives went to meet him to list our demands: to set up a commission to monitor and treat the longterm health effects of contaminated air and water from the disaster; to force Dow Chemical, which had bought Union carbide, to dismantle and clean up the old factory site; and to ensure a supply of clean drinking water to affected communities. The prime minister listened to our demands, but we didn’t get anything out of the meeting except for vague promises.

While I was in Delhi, I got a call from an activist from Bhopal who worked with my brother. She told me that Sunil [my brother] had tried to kill himself again, that he had eaten rat poison and was in the hospital. I thought, He’ll be fine. I thought this because the first time he’d eaten rat poison he’d survived. Still, I took the first train home from Delhi, and my sister and her family were also on their way from Lucknow.

I arrived in Bhopal first, and it was only then that I found out my brother was dead. He hadn’t eaten poison; he’d hanged himself in our apartment. I went to see his body during the post mortem. I was so shocked. I couldn’t stop crying. and then, after a while, I was not even crying. I was just looking at him, in disbelief that I wouldn’t see him alive again. When my sister and her family arrived, my sister actually kind of fainted. and then she was crying terribly. then her children—she had a son and a daughter by then—when they saw her, even they started crying.

After my brother died it was quite hard for me to live by myself in the apartment we’d shared, so in 2007 I decided to move to Delhi. i thought i would go study there, and i enrolled in a crash course in business management. In the meantime i decided to rent out our apartment. So a family moved into my home for the year and a half I was in Delhi. And then when I was ready to move back to Bhopal, I told the family in my apartment, “Either you can share the space with me, or you will have to vacate because I need a place to stay.” They agreed and were happy to live with me. I still live with them—they are really nice people.

I’m damn sure that my brother’s depression was because of the tragedy and the gas that he inhaled that night. He used to say things like, “Someday soon I’ll be dead.” And, “Sanjay, move to Lucknow so that you can live. Our sister, she will look after you. Or better, you should move to a big city like Delhi or Mumbai because I don’t think Bhopal is a safe place to live.” He used to talk like that. Perhaps he did not want me to live around the tragedy. Maybe he knew that his life was ruined because of the past, and that the tragedy was something he could never escape.

I didn’t want to abandon Bhopal. I moved home and dedicated my time to the campaign for victims’ rights. I wanted to be as strong as my brother had been.

Read Sanjay’s full story in Invisible Hands: Voices from the Global Economy.