By Cliff Mayotte

Cliff Mayotte is the Education Program Director with Voice of Witness. He previously edited The Power of the Story: The Voice of Witness Teachers Guide to Oral History published in 2013 by Voice of Witness and McSweeney’s.

“Looking back I think he was kind of a soulful polymath—responding to humanity as he encountered it, in the studio, in the books.”

– George Drury on Studs Terkel

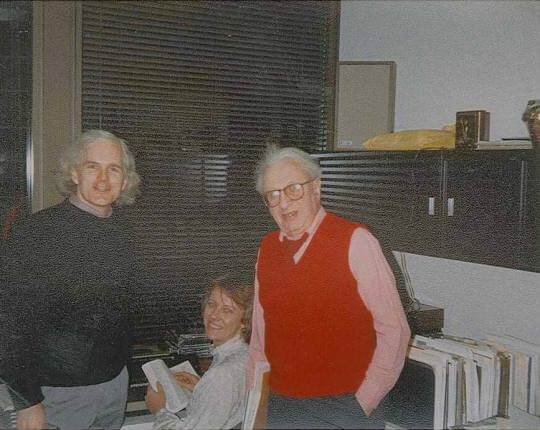

On a recent summer day at the Voice of Witness office, I had the pleasure of sitting down with educator, poet, and longtime colleague of Studs Terkel, George Drury. He happened to be visiting San Francisco during his summer break as a middle school English teacher at the F.W. Parker School in Chicago. George was on a personal trek to retrace the Western migration of poets and writers like Robert Louis Stevenson, Allen Ginsberg, Kenneth Rexroth, and Jack Kerouac. George’s generosity of spirit, sense of humor, and vast personal experience with art and politics made for a lively chat. His reminiscences included many stories and anecdotes about working with Studs at WFMT in Chicago. Among his other stories, it was a delight to hear about the serendipity that brought George and Studs together:

I was working at the National Radio Theater of Chicago. My wife Kathy—many things characterize her, and one of them is her ability to get people jobs. She was working as the program secretary at WFMT. So she would’ve been working with Studs. Yuri Rasovsky, brilliant radio dramatist and producer, had a little hole in the wall operation moving from grant to grant. Kathy said, “Well, Yuri could use some help.” Then Studs, in his peripatetic voice said, “I gotta speak at an event for a retiring doctor. Are there any good poems around?” Kathy told him, “George might know.” Then, gradually, I moved into helping out in the library at WFMT, which put me around him regularly.

Over the next dozen years, these encounters snowballed, as George would serve as archivist, producer, and ultimately as WFMT Spoken Arts Curator, where he provided literary and musical material for shows like The Morning Program, The Midnight Special, and of course, The Studs Terkel Program. George’s reminiscences offered valuable insight into how Studs did what he did, and why he did it. Listening to George was a great opportunity to explore the nuances, complexities, and joys of literature, storytelling, and oral history.

It was also a genuine pleasure to hear George speak of Studs’ passion for listening and human connection—not to mention the skills that Studs employed to help himself achieve this during his interviews. Here are a few highlights from our conversation:

On the experiences that shaped Studs’ skills as an interviewer:

I’ve often thought about the strands that go into his particular abilities. He studied law at the University of Chicago. He had reviewed jazz, and was a serious appreciator of jazz, blues, and folk. All of which are forms that are fundamental, and yet involve constant variation. He’d been an actor and had had serious acting experience, been in soap operas on the radio, and had his own TV show from which he was bumped by blacklisting. He’d emceed shows. He’d lived in a rooming house that his mother ran. He hung around Bug House Square and heard the soapbox people. I think his experience as a kid growing up and being all ears in the boarding house, and then Bug House Square, intuitively convinced him that there’s something to people talking about what they actually do.

The ability to improvise is important, knowing that if you depart from a particular theme or pattern, you’re not going to get lost. In fact that’s kind of where the action is. I think from hanging out with [blues performer] Big Bill Broonzy and other artists, Studs became a good performer who understood that you don’t do things by rote. Maybe from pride, he wasn’t going to accept a prefab list of what to ask someone. It was going to be an event.

On how Studs prepared for interviews:

He read in advance. He would be a reader beyond the instance of the one book that he was reading to prepare for the conversation. Studs was no anti-intellectual. And then he would, like a good improviser, read the situation of the exchange with the person. I also think Studs had to stay adept because he didn’t just talk to famous people, he also talked with those he would refer to as the non-celebrated… That variety of encounters is really something that long-term is very difficult to fake.

On storytelling and the need for human connection:

In a letter, Studs writes about radio and an identifiable presence. He’s saying, “Look, people like to know that someone is there,” reliably there. It’s a very deep human need. We can’t become aloof from that… The work wasn’t a matter of pretending to do something, it was a matter of actually doing something. That is the distinction, I think, that he makes. More and more, in broadcasting, say, you can have very, very proficient people who are in a sense playing a game very well, but nobody is present. There’s nothing really happening there.

On Stud’s groundbreaking work as an oral historian:

He’s a respected figure now, largely, but there are some people, some academics, and all sorts of people who don’t count oral history, don’t grant it any kind of standing. He had to be beyond aware of that, because people weren’t always nice about his work or forthcoming about it.

He would interview some people, and help them only to have at least one of them, later, refer to him in print as the “noted tape-recordist.” That’s like saying that Babe Ruth was a baseball player. Studs really did establish the field in a huge way, in a way that’s now viable. It’s recognizable. But I don’t think he ever felt fully embraced by the academic world. And then he won a Pulitzer Prize. He sort of proved the point.”

On the impact that Studs has on George’s own work as an educator:

Every class that I teach—and I’ve always done this—I begin by asking, “Does anybody have anything to read or share?” I usually have something, and I might use it, but if the students have things—it could be anything—from the newspapers, a poem, something from their journals, or whatever interests them… Every class period. That’s how we start. So there’s my activity du jour. It acknowledges that we’re all there, and some pretty distinct and useful things have happened that way. And so I think that that’s very much in the spirit of the thing. “Let’s keep going here, but what have you got?”