by Jon Earle

A bride and groom are married in chains. A mother prepares her daughters for life without her. Two prison friends sing, “Lord, give us a big heart to love, and a strong heart to fight.” These are the stories of immigrants facing deportation right now in New York City. Since January, volunteers at the New Sanctuary Coalition, a New York–based advocacy group, have been recording these stories to bear witness and advance the cause of immigrant rights. Having recently recorded our twenty-first storyteller, it seems like an appropriate time to reflect and share our experience.

Our project began in a state of emergency. As the Trump administration’s deportation efforts intensified, members of our community began disappearing at a terrifying pace. In January, New Sanctuary cofounder Jean Montrevil was deported to Haiti, and executive director Ravi Ragbir was detained at a routine ICE check-in. Scrambling to fight back, we decided it was time to stop planning the perfect storytelling project and start recording.

Some of what we’ve found has surprised us. We didn’t realize, for instance, how big a problem unscrupulous immigration attorneys are. Almost every person we’ve interviewed has a horror story. Isabella* paid over $8,000 to a lawyer who, in court, faked a coughing fit to avoid answering elementary questions from the judge. Ilona ended up paying $15,000 for her lawyer to file a single piece of paper. “Not even the basic USCIS paperwork. Nothing. Nothing arrived to where it was supposed to. Nothing happened,” Ilona told us. We hope that investigative journalists and prosecutors will look closer at this apparently widespread fraud.

We’ve documented experiences and anxieties common among immigrants deemed “deportable” by the government. Like Kalisa’s experience of “coming out” to her teenage daughters about her immigration status. “I didn’t want them to know,” she explained. “It was almost like, ‘Let me shield them from this.’ But then I was stressed all the time and I’m struggling.” Or Keith’s struggles with his ankle monitor. Keith was on a city bus when the “bracelet” malfunctioned. “And the bracelet is like, ‘Your bracelet is dying! Charge your bracelet! The bracelet started speaking to me.’” he recalled. “I had to run off the bus, you know, because people is looking at me.”

Several interviewees have lived in the United States for decades and had their green cards revoked after criminal convictions. These are the “criminal aliens” that fill the pages of the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) e-newsletter. (“ICE Arrests 45 in Houston Area during 5-Day Operation Targeting Criminal Aliens, Immigration Fugitives,” read the top headline of a recent edition.) To be sure, violent criminals have been caught in ICE’s ever-expanding nets. But among America’s “criminal aliens” is Kalisa, the mother of three, a practicing nurse and devout Christian whose two-decade-old marijuana convictions—for which she served her time—hardly seem like reasonable grounds for deportation. “I feel like I have to prove myself beyond proof,” she told us. “Why does it have to take that much?” Sitting there, listening to her, we wondered: Why is it so hard for us to welcome imperfect people into our imperfect nation?

The immigrant experience that we’ve documented often boils down to an internal struggle between hope and despair. Storytellers describe languishing in immigration prison, wondering whether they’ll ever get out. They talk about the “never-ending rollercoaster,” as one put it, of ICE check-ins and court hearings, with naysayers and boosters at every turn—the lawyer who says, “You don’t have a chance,” and the pastor who says, “Keep fighting.” A supportive community can make the difference between giving up—agreeing to leave the country—and digging in. For many, New Sanctuary is that community. The organization provides technical assistance with asylum applications—and also moral support. Members accompany immigrants to their hearing and check-ins, making sure that they’re not alone in their most vulnerable moments. We see our oral history work as part of that. Each interview is an attempt to rehumanize, to deeply connect, and to give the gift of being heard.

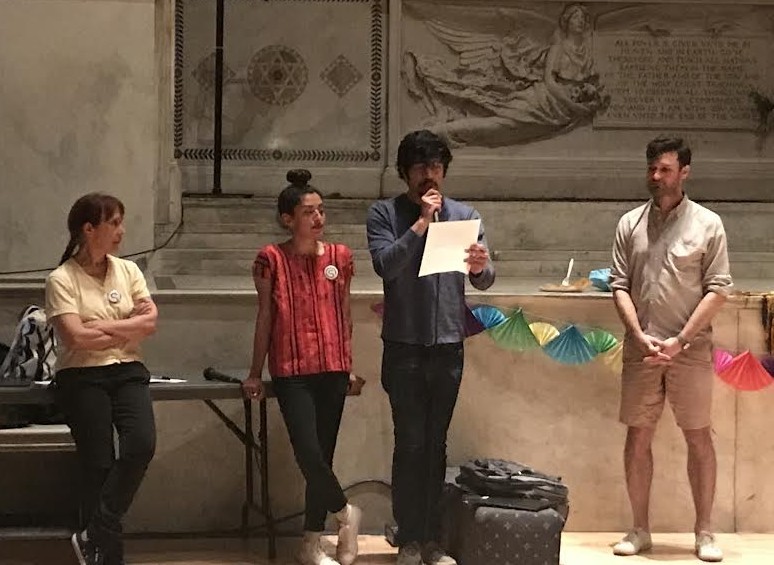

A note on process: Our team of six has been extremely fortunate to have support from within New Sanctuary. Two members work closely with New Sanctuary to identify potential interviewees. A potential interviewee shouldn’t be in “emergency mode”—rushing to file an asylum application, for example—and should be comfortable in the New Sanctuary community. There really are no other criteria. Perhaps in the future we’ll have to limit the scope of our project, but for now, we’ll sit down with anybody who wants to share their story. We record every week for 60–90 minutes on the sidelines of regular community meetings. Our interviewing team is bilingual (Spanish and English), includes men and women, and is US- and foreign-born. Moving forward, we hope to bring narrators onto to the team to help us ask better questions and make sure we’re respecting and empowering interviewees at every step.

But the truth is that we empower each other. Narrators and interviewers. Our team has already witnessed more strength, courage, and resilience than we could have imagined. We have seen men and women move from the shadows into the spotlight, and from fear to fearlessness. We’ve met people who have gone from barely knowing English to mastering American immigration law. And we’ve recorded masters in the art of survival and even thriving under unimaginable pressure. You can’t hear these stories, week after week, and not feel your resolve strengthen. That is empowerment, too. And that’s the great hope of our project, that by sharing these stories with as many people as possible, we spread more than simply information—what it’s like to be deportable, and so on—but to have conviction and resilience as well.

As we approach thirty and hopefully many more interviews, much remains to be done. We’re exploring a podcast. We’re pitching stories. We’re looking for creative collaborators and outlets that can bring these stories into ears, eyes, and hearts. And we’re thinking about how we can design the next steps to support community and narrator agency. Funding and project scope challenges remain: Should we interview volunteers? ICE officers? Wherever we go from here, we go empowered by our friends and dedicated to their service.

*All names have been changed.

Listen to a two-minute clip of Kalisa’s story

Listen to a two-minute clip of José’s story

Jon Earle is a Brooklyn-based documentarian and Russian translator. His audio work has aired on KCRW and NHPR, and appeared on the Spotify podcast “United States of Music.” He produces “Success @ Sinai,” a podcast for the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Jon is an alumnus of the Transom Story Workshop and the Oral History Summer School.