By Fanny Julissa García

Fanny Julissa García is an oral historian and narrative change strategist. Last summer, she worked as a consultant for Voice of Witness. She shares her independent work here as the project director for Separated: Stories of Injustice and Solidarity, which began in 2019 in partnership with history professor Nara Milanich. Below, Fanny reflects on how the project has incorporated applied oral history methods.

In the summer of 2018, news broke about the US government’s adoption of a radical new policy to separate parents from their children at the US–Mexico border as a form of immigration deterrence. The situation provoked anger and mobilized tens of thousands around the country. The administration was forced to rescind the policy within weeks, but the damage had been done. Border agents separated thousands of families. The government forced parents to return to their countries of origin while their children remained in the US, resulting in months or years of separation.

Separated: Stories of Injustice and Solidarity documents this historic human rights violation. It records the stories of mothers and fathers and daughters and sons to ensure their experiences are not forgotten. Since the project began in 2019, we have recorded more than thirty interviews with parents and seven interviews with children. All the interviews took place through telephone conversations and employed a dynamic verbal consent process. We use the term “dynamic” because we asked each narrator why they wanted to share their story and how they wanted it used or disseminated. These two simple yet essential questions created an exchange focused on respect for choice and personal agency. Every person had their own unique response, but almost all the families responded that they wanted their stories to help advocate for ending family separation. One mother we interviewed stated:

“I would be willing to tell my story a thousand times over because I don’t want this to happen again, especially with my people. We are human beings.”

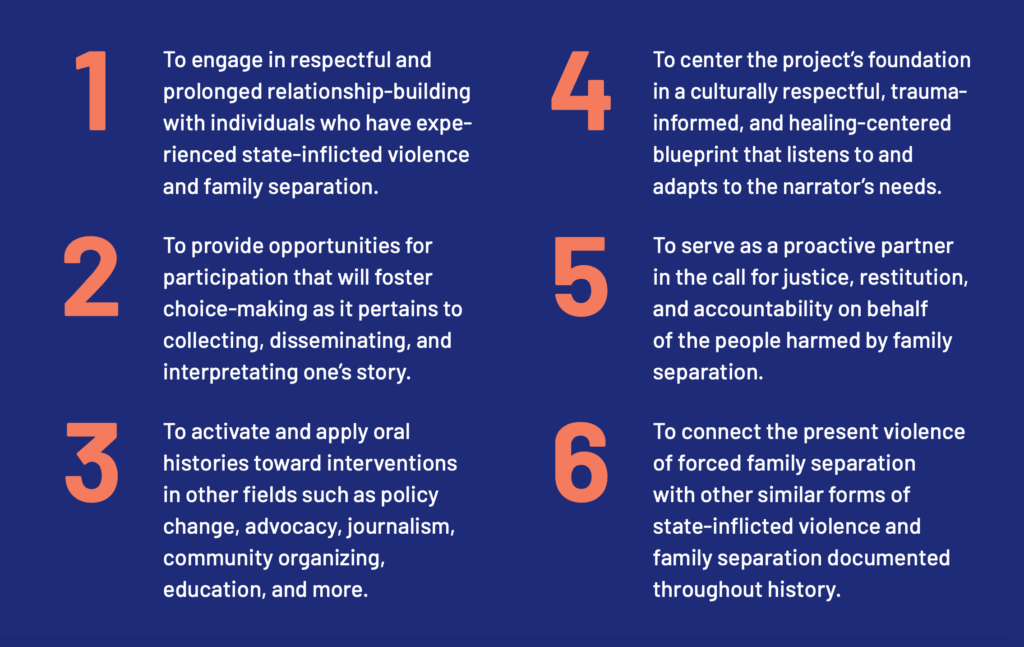

The dynamic consent process also made us (the project’s oral historians and interviewers) more aware of the responsibility and care the project needed. Suddenly, we were not just recording interviews for posterity. The narrators were tasking us to do something with their stories and commit to their intentional dissemination. This process motivated us to develop and implement “applied oral history” methods to the project design. Applied oral history is influenced by the oral history for social change practices championed by oral historians such as Alisa del Tufo, Virginia Espino, Gabriel Solís and many others. Their practices use oral history and narrative creatively, effectively, and ethically to support movement-building and transformative social change.

In applied oral history, the first goal is for the research to serve the people.

It seeks to serve the community whose members are contributing their life histories and experiences, and to raise consciousness and contribute to policy change aimed at social justice and equity. We created the following set of commitments to remind us of the level of responsibility we have toward our narrators:

Using applied oral history methods helped us ensure the active participation of the narrators in all aspects of the project, not just the interview. It also provided a process to explore the long-term relationship needed to care for the project past its documentary stage and into its activation in service of the families who contributed their stories and experiences.

Many practitioners use some form of long-term relationship engagement with narrators for oral history projects. Relationship building is needed to ensure the active engagement of narrators and to make the process less transactional and more relational. Still, we have rarely explored the deep commitments required to make this possible. Applied oral history is one method we can use to start exploring this more intentional process of documenting and preserving oral histories of people and communities who have experienced some form of state-inflicted violence.