We’re launching a new quarterly interview series exploring how practitioners develop and present oral histories across different formats to create impact.

Through these articles, we’ll delve into both traditional techniques and innovative digital approaches, examining how different media can make oral histories accessible to various audiences. Our first interview in the Activating Oral History: Dynamic Approaches to Storytelling series features public historian Yolanda Hester.

Yolanda’s oral history project, article, and digital exhibit on Black entrepreneurship in Los Angeles caught our attention for their documentation of intersecting narratives around business, civil rights, and community life, while addressing key project-related questions about motivations for participation, narrator compensation, and community engagement.

This work takes on particular urgency given the historical vulnerability of Black-owned businesses, from the devastating destruction of “Black Wall Street” during the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre to the recent fires that wreaked havoc on many historic Black-owned establishments in Altadena, California. Among the losses was the Little Red Hen Coffee Shop, whose owner contributed an oral history to the project before the business was destroyed in LA’s Eaton Fire.

In this interview, Yolanda delves into how Black-owned businesses have historically served as more than mere commercial enterprises, functioning as vital community centers that provide social, political, and economic support to their neighborhoods.

At a time when Black-owned businesses continue to face systemic challenges and physical threats, Yolanda’s work is a crucial contribution to understanding and documenting the resilience and essential role of Black entrepreneurship in the United States.

Yolanda, please share your journey into oral history and public history work. What drew you to these fields and ultimately to the research and writing that led to your article “Community and Commerce: Oral Histories of Black Business in Los Angeles” published in The Public Historian?

My entry into oral history started first and public history a few years later. I was working in the arts with a focus on community based projects and I wanted to capture authentic stories and voices. I had long been familiar with oral history methods but had not been formally trained, so I took my first class at UCLA roughly 20 years ago.

As for public history, I had been interested in history since I was a kid, but didn’t learn about public history as a field until I was an adult. It was through my community-based work that I started to learn and realize how crucial public history was to the community work I was doing. It would compel me to go back to school and get my graduate degree at UCLA.

While in graduate school, my research focused on cultural designation policies in ethnic neighborhoods, and during that research I learned a lot about the relationship between communities and the local businesses that support them. I became intrigued by that dynamic. I have a history of small business ownership in my family, so there was a personal connection, too.

What I found particularly interesting was how little the voice of small community-based businesses, “mom and pop” shops, show up in community history projects despite being anchors or the “economic glue” that holds a community together.

Although, traditionally, businesses are seen as private institutions, I noticed that Black businesses functioned in many ways like public institutions providing social, political and economic support to their communities. And I wanted to know more about that and gain a better understanding of that dynamic.

I was also interested in the staying power of the businesses I ran across in my research. Los Angeles County has a long history of Black business ownership going back to the late 1800s. I wanted to understand how those businesses weathered change.

In this project, the oldest business goes back as far as the early 20th century with the fourth-generation owner still active. This allowed me to reach back historically pretty far. All of the participating businesses were at least 25 years old and roughly half are 50 or more years old, which meant that they survived through a rapidly evolving and frenetic period of history—the Civil Rights Movement, Women’s Movement, Vietnam, the Reagan years, HIV/AIDS crisis, massive technological changes, etc. I was fascinated by the stories that could be shared. But mostly I was interested in the people—behind all of the businesses are these wonderful people who I was able to learn from. African American entrepreneurs have always had to strategize around a racialized marketplace. I was interested in learning how they navigated those challenges.

Your article emphasizes the narrators’ various motivations for participating in this project and how you navigated the question of narrator compensation. How does understanding these motivations shape our view of narrator autonomy, and why was it important to highlight this aspect?

When I first embarked on this project, I hit the ground running and literally went “door to door” to find narrators. I thought this was the best approach for busy entrepreneurs. But what this meant was that I ultimately met the owners on their turf and on their terms and that they were able to assess the project in real time and determined whether I or The Center For Oral History Research at UCLA (COHR) were worthy recipients of their stories. They were savvy business owners who knew clearly their worth, how they valued their time and were used to doing cost analysis assessments. They could determine the value of the project in supporting their own needs and agendas. To that end, I would say the project was collaborative.

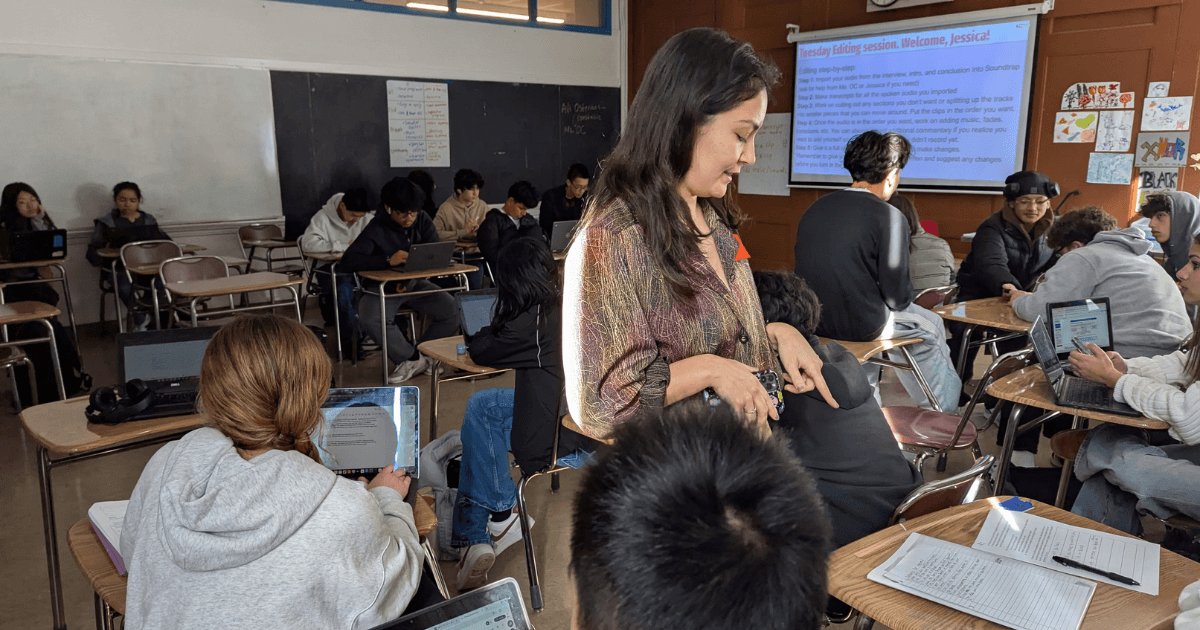

In fact, when the oral histories were curated into a digital exhibition, narrators contributed archival photos from their personal collections. And post project, narrators found their own uses for the work, whether it was used for networking, preservation, marketing, or honoring the life of a narrator who had passed away. One narrator sponsored a gathering at his restaurant so that some of the narrators could strategize together (see photo). And families of two of the narrators who have passed away used the oral histories for their memorials.

We did not financially compensate the narrators, although we felt strongly that the project should be beneficial to them. Compensation is important, but I also learned that there are different types of compensation and the context of the project and profiles of the narrators are important to consider, much like the theory of “situated compensation,” which advocates for compensation but encourages oral historians to think about context.

And to be honest, with our budget, we would not have been able to pay the narrators what they are worth and were thrilled that narrators had their own motivations for participating. In the article, we discuss this more at length, but one appeal, especially for the multi-generational family businesses, was the opportunity to comprehensively document and preserve their family history, something that they would not have had the time to do on their own. Some of the businesses saw their participation as another way to get the word out about their businesses. Most felt that the wisdom they could share would be of benefit to their communities and younger entrepreneurs.

How did your project evolve from an oral history archive to its digital presentation, and what future forms do you envision for it?

When the Center For Oral History Research welcomed me back to develop the project into a digital exhibition, I was thrilled. They were interested in finding ways to activate their collections and Community and Commerce was chosen to be curated into a digital exhibition. This presented a new opportunity in terms of accessibility for the project.

As a digital exhibition the oral history series would reach a broader audience and would be more useful for educational purposes. And curating the exhibition gave me an opportunity to dig deeper in my research and contextualize the recordings with essays and archival photos.

As for the future formats, I would like to see the material in a physical exhibition. I’m also particularly proud of a podcast I did for Councilman Marqueece Harris-Dawson on the project. Many of the businesses are in his district. I think there are many possibilities. And I hope the narrators continue to utilize the work.

Access the article in The Public Historian.

View the the online exhibition (use Mozilla Firefox for an enhanced experience).

About Yolanda: Yolanda Hester is a public historian, oral historian and co-founder of the consulting firm, Frameworks and Narratives. She is featured in the PBS series: Changing the American Doll Industry, and in the Netflix documentary, Black Barbie. She has worked for many organizations, including the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs, Local Projects, the Urban Civil Rights Museum, The Center for Oral History Research at UCLA, and the Forest History Society’s digital exhibit – Reclaiming Maxville: The Legacy of African Americans in A Lumber Town. Hester is the Project Director of the Arthur Ashe Oral History Project, an initiative of Arthur Ashe Legacy at UCLA.

Partner with VOW

Voice of Witness offers expert storytelling and program support to organizations, educators, advocates, artists, and more. These collaborations harness the power of oral history to promote community building, learning, and action. We work with partners to develop customized, interactive workshops and projects using our award-winning methodology to advance your mission.