This quarterly interview series explores how practitioners develop and present oral histories across different formats to create impact.

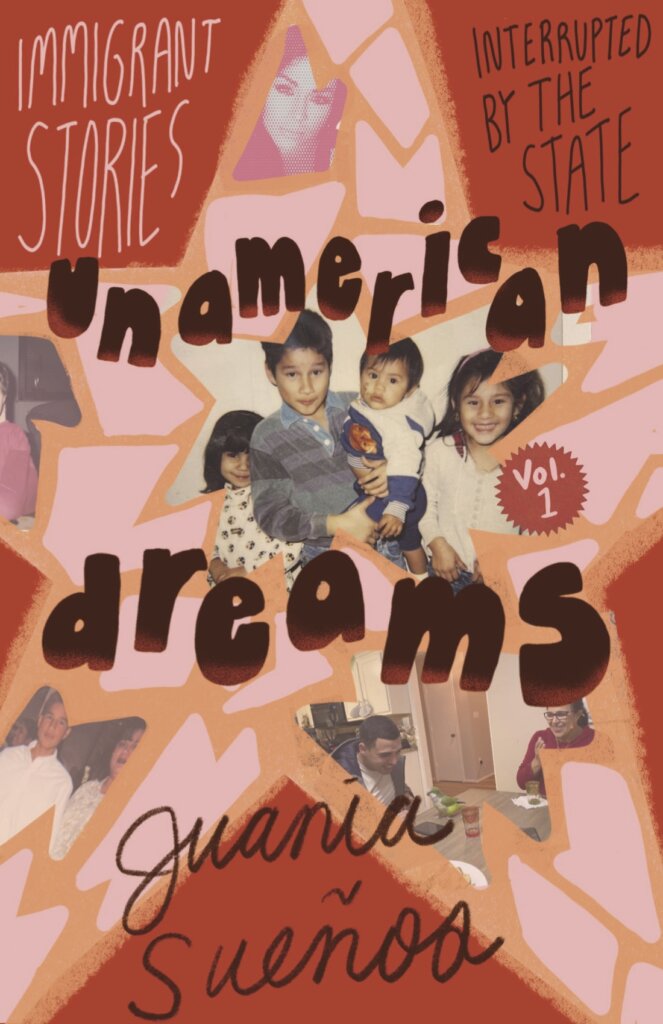

For the second interview in our Activating Oral History series, we’re featuring the work of Juania Sueños, a queer Chicanx writer, educator, translator, mother, and community advocate. In 2023, she published a zine of testimonios titled UnAmerican Dreams: Immigrant Stories Interrupted by the State. The zine was created as part of her fellowship with After Violence Project, during which she documented the lived experiences of Texans impacted by state violence.

The zine is a beautiful example of the interconnectedness of oral history, testimonio, literature, and art to activate stories beyond the archive. Through this blending of mediums, Juania demonstrates how oral history can move beyond just documentation into an act of creative expression, collective healing, and resistance.

“This project began as a wish to honor people I care for deeply (half of them family members) who lost the privileges I now hold: freedom, certainty in legal status, & the ability to cross borders. Though each section is unique, they share a depiction of the ways in which the United States’ ‘justice’ system atrophies the spirit.”

For Juania, choosing to call these stories “testimonios” rather than interviews was deliberate. She explains that “testimonio” carries political weight that “interview” lacks. “For so many centuries our stories [colonized peoples’] were recorded by others, in their words,” she notes. In contrast, testimonios offer autonomy and recognize personal narratives as authentic history that can reveal larger truths about systems of oppression.

“UnAmerican Dreams” deliberately avoids what Juania calls “trauma porn” – work that reduces marginalized people to their suffering for outsiders to consume. Instead, the project incorporates drawings, photographs, and poetry alongside stories that honor joy, dignity and complete lives.

Please tell us about yourself and the relationship you have with writing. Additionally, why did you choose to call the collection of interviews and narratives in UnAmerican Dreams “testimonios?” What is it about testimonios that evoke a deeper commitment to speaking out?

So, I didn’t begin writing until I was a junior in college. By that I mean writing creatively. I suppose I didn’t feel I had anything to say let alone the authority to write! That seemed reserved for upper middle class people who wrote in their studio drinking coffee all day. That couldn’t be further from my background and reality.

It wasn’t until I was introduced to Chicana writers like Gloria Anzaldua, Cherie Moraga, Julia de Burgos, Elena Maria Viramontes, that I started realizing, oh shit, this art form also belongs to me! It sort of evolved from there.

I decided to pursue an MFA in Creative Writing to learn more about that world of badass Chicanas taking on macro socio-political issues by writing from their heart, imagination and intellect. I didn’t wind up learning much more about them through the program I chose, I found them, I’m still finding them by, funny enough, conducting interviews with contemporary Chicana figures, but that’s a different story.

When I think about the word “interview” there’s this connotation of power dynamics at play. Somebody is in control, the interviewer who is in charge of where the conversation goes, and another is at the whim of the questions. For so many centuries our stories [colonized peoples’] were recorded by others, in their words, what they perceived was accepted as history. “Testimonio” has such an incredibly rich history in Latin America, beginning with constant political turmoil–as we know, a lot of it caused by the United States’ involvement.

People were literally giving testimonies to governments to avoid persecution, or aid an opposition. Then this idea of personal narratives being outwardly political was more popularized during the civil rights movements where by telling their stories people would find commonality and spot systems of oppression. There was the famous “The personal is political” slogan. Then this was really absorbed by marginalized people who’d been sort of spoken for for so long! This new idea that our testimonios are history. They point out bigger truths: injustices, systems of oppression. Personal storytelling offers a sense of autonomy within that.

I was very intentional about using that term, especially as a fan of Elena Poniatowska’s works, which have gravely informed my idea about “interviews.” She interviewed hundreds of people, all kinds of people, many working class, after towering disastrous happenings, like the 1981 Mexico City earthquake, and the student massacre of 1968. There was a lot of gaslighting happening during those tragedies on behalf of the Mexican government. So she decided her role as the author was giving up that position. She was more of a transcriber, bearing witness to the effects of these terrible events by hearing people who experienced it first hand, their testimony as the truth over whatever the Mexican government claimed, over whatever the media wrote, over whatever the rich said. Their testimonio was the real history. A testimonio is political, it’s loaded. An interview isn’t.

The zine incorporates multiple forms of expression—drawings, photos, and oral history interviews. What guided your decision to use this multimedia approach, and how do you feel these different elements work together to convey experiences that might be difficult to express through words alone?

I think a big consideration I try to have when having these conversations is understanding that not everybody’s means of expression is the same. It looks like writing for me, and talking to a lot of people, but some folks, especially around traumatic experiences, tend to have more complex mediums of working through things. A lot of it came about organically as well.

For example, Jose told me about his tattooing and drawing and that’s when I asked him if he had any samples he’d like to include with this testimonio. Same with Jayden. When she described moments of her childhood, oftentime the joyous memories were so vivid and descriptive and she mentioned something like “oh yeah, there’s a picture of me with the little sparkly Dorothy shoes on.”

So those were the visual items I wound up using. I also included a poem because the interviews with Jayden took place over several weeks, and her birthday happened between that time. I had the opportunity to sit with her story and as a form of healing for me I wrote her a poem with her as the speaker and gave it to her as a birthday gift.

She was so touched by it, I don’t think because I’m that good, haha, but because she didn’t expect the level of connection with me. I’d been introduced to her as doing these interviews for a “project” and this goes back to that notion of a preconception of the interviewer’s role. I think you get the best testimonios when you make a genuine personal connection and it creates mutual trust.

The zine is an excellent example of what can be created when we use a trauma-informed and healing-centered approach to storytelling because it features instances of joy, love, and transformation . How did you do this and why was it necessary in this work?

That’s a difficult question to articulate in a succinct, sensical way! I think, in essence, I was so tired–am so tired–of these trauma porn works targeting an audience staggeringly far removed from an oppressed person’s experience! I was thinking in particular of media that makes a subject out of a person with a story that within a given period of time is perceived as topical.

Just like, hey we, free citizens full of other privileges, want to know about what it’s like to be this undocumented or incarcerated victim so we feel in the loop when the media references it, so do tell us yours in the most reductive way possible. Reduce yourself to your traumatic experience just so somebody doesn’t have to do the work of learning through other methods, and not for this instant gratification of, phew, okay I know about this identity from consuming one painful telling of it, work done, guilt dismissed. It’s like, no. Thank you for your interest but this isn’t for you to consume.

I could go on about this predatory dynamic between marginalized people and these other parties trying to produce something from their pain. I was very intentional about not focusing on anybody’s trauma inflected by State violence, though ironically that was technically my assignment. I think there’s a bigger conversation to be had even in abolitionist movements on how to pave a way to change without beating confessions out of directly impacted folks–I went through that enough during my young adulthood.

I’m always pushing back on this idea of getting a vision or a reality across to make change by skimming through the details. It’s like when you read a novel like The House of Spirits by Isabel Allende about the coup d’etat against the socialist government in the 70s. You don’t remember the exact years, or the exact names of governors and senators and the names of the different targeting laws. You remember the main character’s familial dynamics, how not only their physical life changed, but so did their spirit because of these political cataclysms. I think that’s what art should do. Create human depth!

Within UnAmerican Dreams, I don’t believe anyone goes into specifics of their getting put in a cage or losing a family member. I tried leading our conversations into a place of that connection I was talking about earlier! I’m not a therapist, and I didn’t pretend to be one, but I was trying to build a meaningful relationship. I really believe it helped me and everyone process difficult emotions around the labels and harm these systems had inflected. We put it into a bigger context, creating a picture of a whole individual.

I made sure everybody’s testimonio touched on childhood. On origins. I wanted to witness a life’s journey, not the current physical place limited by cages or borders. Telling your life’s journey inherently lends itself to transformation. Each time we tell our story, we learn something new, spot something different, have different questions, construct different significance, a new meaning. I didn’t do anything to allude to any transformation, that was a side effect of allowing somebody to meander, to go everywhere with their “answers” to a question! That was not me at all.

View a digital version of UnAmerican Dreams: Immigrant Stories Interrupted by the State. Listen to the oral histories conducted for the making of the zine. The zine is also available for purchase.

About Juania Sueños: Juania is a queer Chicanx writer, educator, translator, mother, and community advocate. She co-founded and is an editor at Infrarrealista Review. Her work has appeared in Acentos Review, New York Quarterly, Sybil Journal, The Skink Beat Review, Porter House Review, Nat. Brut, and the Westchester Review. She is a migratory bird from Zacatecas. Her experience growing up undocumented in the U.S. has and continues to shape her work. She was the 2019 recipient of the Editorial Fellowship from the Center for the Study of the Southwest. She was the 2021 Visions After Violence fellow and the 2023 Writer in Residence at the Texas After Violence Project. On her desk sit many peculiar, sidewalk-found objects, an MFA diploma in Creative Writing from Texas State, and other boring credentials given to her by institutions. Her hybrid memoir Topography of a Borderline Bird is forthcoming from Mouthfeel Press, 2025.

Read the first interview in our Activating Oral History series with Yolanda Hester.