by Eliana SwerdlowThe human rights crisis at the United States and Mexican border sits at the forefront of my consciousness.

As I go about my daily life, I think of the stories of many individuals who are suffering at the hands of the American government. As the media reports, we’re at a dangerous moment during which we’re asked and inspired to react. We’re asked to witness and react to the photograph of Salvadoran migrants Oscar Alberto Martínez Ramírez and his daughter Valeria who drowned along the banks of the Rio Grande.  The truth—and I think many would agree—is that these injustices at the border are not new. Yes, they are worthy of all the coverage they’ve been receiving. That coverage is important. It is essential. However, the news isn’t groundbreaking in that we, as Americans, are asked every day to consider migration and citizenship.

The truth—and I think many would agree—is that these injustices at the border are not new. Yes, they are worthy of all the coverage they’ve been receiving. That coverage is important. It is essential. However, the news isn’t groundbreaking in that we, as Americans, are asked every day to consider migration and citizenship.

In every presidential election for which I’ve been alive, immigration has been a central issue. I cannot imagine it slipping into the periphery because these themes of migration and citizenship are woven into our historical fabric. For better or worse, they are the basis of our nation.

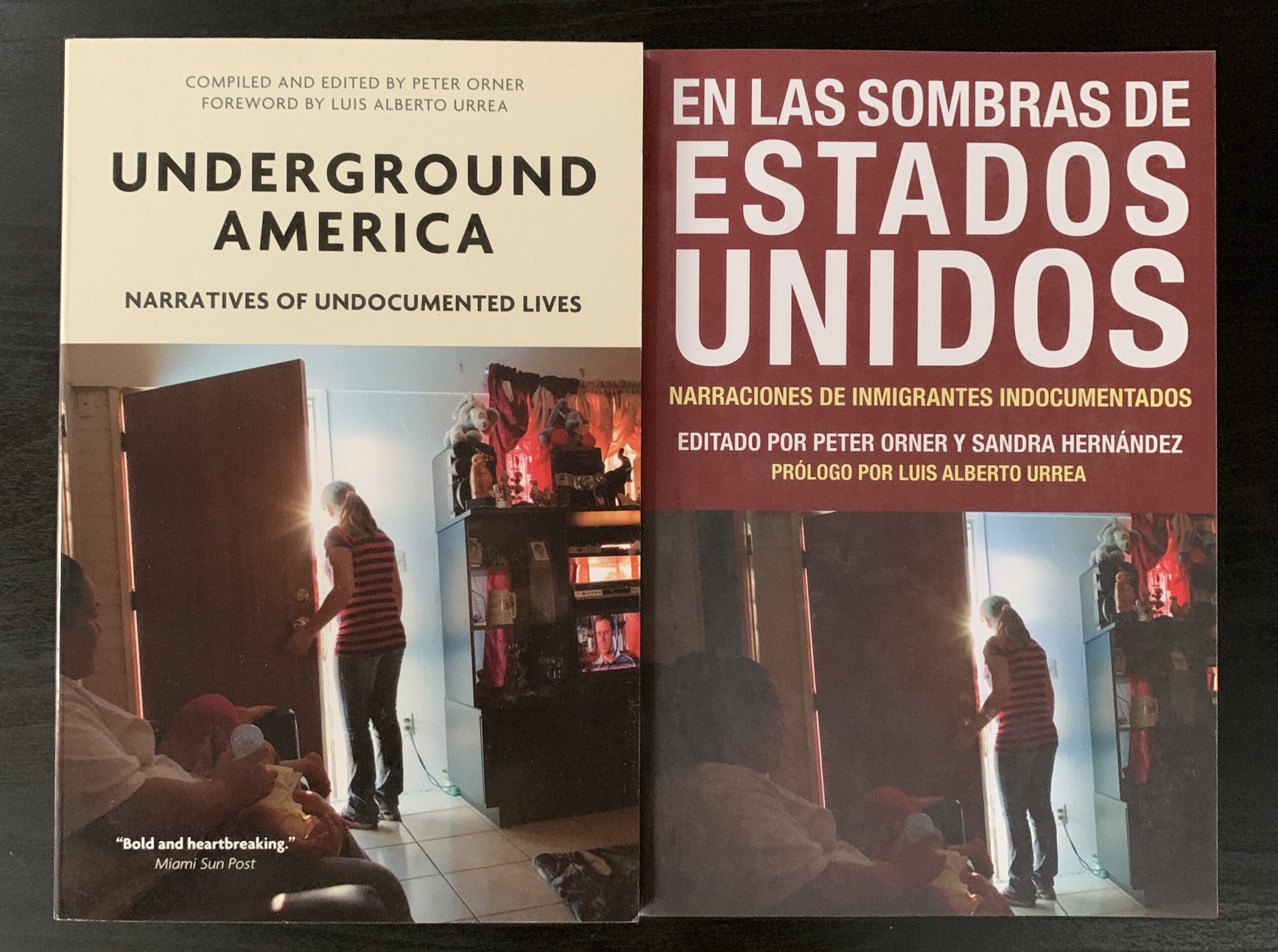

Given the amplified national conversation about migration and citizenship today, I was inspired to go back to Underground America, which was published over ten years ago, as a resource to better inform me about the perpetual conversation. I read Underground America with the hope of seeing how today’s conversation echoes back to the book’s ideas and stories.

Unfortunately, going into the book with this goal proved to be a deflating experience in that, at first, it seems like not much has changed in eleven years. As I read these stories, I kept thinking that, for example, what happened to Victoria in Olga’s story might be happening to someone else right now.

Also, borders remain arbitrary, just as Abel expresses in his story: “The terrain didn’t seem any different from one side of the border to the other. It was the same land to me.” Finally, as many narrators reveal in their stories, I can’t help but be convinced that immigrants continue to be exploited in the workforce.

In the midst of my time spent reading Underground America, I attended the Lights for Liberty protest outside of New York City Hall. There, as has been portrayed in the media, the detention centers at the border were compared to concentration camps. As people chanted the words “Never Again,”—a phrase always tied closely to Holocaust remembrance—I felt ashamed.

In the midst of my time spent reading Underground America, I attended the Lights for Liberty protest outside of New York City Hall. There, as has been portrayed in the media, the detention centers at the border were compared to concentration camps. As people chanted the words “Never Again,”—a phrase always tied closely to Holocaust remembrance—I felt ashamed.

What’s happening at the border is not only an echo of a genocide, but also a continuation of the injustices many of the Underground America narrators recount in their stories. As depressing as this comparison was for me, I felt a strong surge of hope when I saw a sign with a photograph of Anne Frank being held up by a woman in front of me. It quoted Anne Frank, “What is done cannot be undone, but it can prevent it happening again.”

Perhaps it was because these words came from Frank, one of the most influential writers in my life, that I felt hopeful as I was reminded of the strength and necessity of bearing witness. It’s my personal experience that bearing witness to one injustice is a proactive measure in that it forever changes how I react to the injustices the media highlights today.

As I read The Diary of Anne Frank again, while continuing to read VOW narrators’ stories, I see that the phrase “Never Again” not only refers to the promise to never persecute other persons in prejudice’s name, but also to the promise to never neglect the shared humanity of all people. It’s a promise to think and do under empathy’s guidance.

Everything that these VOW narrators have endured cannot be undone, but their brave choice to share their stories is, I believe, a proactive choice. Individually and collectively, these stories represent truth—both about the nature of injustices and our fundamental humanity—that is worth internalizing so that when the next injustice appears in the media or in our neighborhood, we react in the most thoughtful way. We react in remembrance and accountability.

It’s that internalization of truth that transforms the reader, too, from simply reader to witness. It’s my hope that if we are in the practice of empathetic witness to people’s oral histories, we can proactively position ourselves to better react to today’s injustices. Reading Underground America and other VOW books, I am inspired to not shy away from historical or contemporary truth. Instead, as a witness in my own way, I seek it.Eliana is a summer intern at Voice of Witness and a rising junior at Yale University.