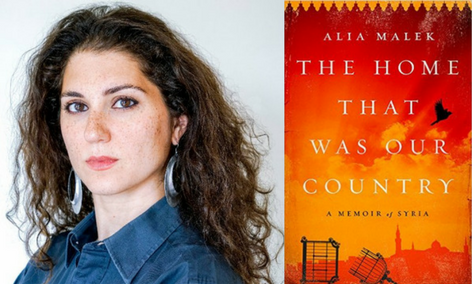

Photo: Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

In her new book The Home That Was Our Country: A Memoir of Syria, journalist Alia Malek (editor of Patriot Acts: Narratives of Post-9/11 Injustice) recounts her journey to reclaim and restore her grandmother’s apartment in Damascus at the start of the Arab Spring.

We recently had the chance to talk with Alia about this rigorously researched and deeply personal new book.

We asked her about her writing process, her sources of inspiration, how she wove together personal history and public history, and why this is a topic that should be on readers’ minds now.

We hope you enjoy the Q&A that follows!

EVENT

Alia Malek in conversation with Micheline Marcom

May 8, 2017

Green Apple Books on the Park in San Francisco

Click for details

A Q&A with Alia Malek

by Natalie Catasús, VOW Staff

The book takes an ambitious and multifaceted approach to its subject, drawing from your background in journalism, oral history, and law. Can you say a little bit about how these different aspects of your writing practice influenced the project?

Well, having a legal background has taught me to not be afraid of research! And it also means, I think, a certain intellectual flexibility to be able to see matters from many different perspectives. First, I had to piece together the family history, and second, really learn Syrian history in much more specific terms than just the broad strokes. I had to scrutinize family legend and see if it could be confirmed with the events that they purported to describe. And with the help of academic sources and the scholars themselves, I had to try to understand what people were thinking in the moment and in the times they were living, not how they had learned to tell it or remember it years later. And with history so contested in the Middle East—between the competing nationalisms and axis of identities—that was not so easy.

The work is ultimately a piece of narrative journalism—that’s rooted in deep research. I’ve found that good storytelling is one of the ways to make a story that seems really complicated accessible to a broader audience. It also helps lower people’s resistance to seeing Arabs or Muslims or Syrians as human beings, as opposed to whatever negative caricature we’ve long grown accustomed to.

As for oral history, I’ve long found that medium to be one of the best for breaking down a reader or listener’s resistance to engaging with a subject or a people. I love what VOW does, and I remain so proud and honored to have been part of its work. I also was very lucky that a historian of my ancestral village had taken oral histories from survivors of the many horrors of the First World War in Syria. They were essential to helping me understand the ethos of a time that is now a century behind us. While my book is not a collection of oral histories, it tries to take what I love about that medium—people speaking in their own words—and apply that as much as possible to when I represent other people’s lives in my journalism.

In the prologue you allude to the fact that as the American child of Syrian immigrants, who also holds a Syrian identity card, you occupied a complex position during your time living in Damascus, straddling the line between insider and outsider. How did you go about building trust with the people you interviewed for this project?

To build trust in any interviewer/interviewee relationship I always go with complete transparency. I explain what I am doing and why I am doing it. I’ve heard other journalists try to coax people to be interviewed by telling them that talking to a journalist will improve the lot/fortunes of the interviewee. I don’t make those kinds of promises. I also let the work I have done speak for itself, and they can easily find it online. I told people in Syria I wanted to write a book about my grandmother, which for many was incomprehensible, as she was just an ordinary Syrian woman. And when challenged, which I expected, I’d answer honestly as to why I wanted to do this—I felt the real story of Syria lay in its people, not only in the deeds of the men who had dominated it. And then I left it to the person to decide if they wanted to participate.

As with much oral history work, some of your previous books like the VOW title Patriot Acts: Narratives of Post-9/11 Injustice required you to focus your writing on the experiences and voices of others. What was it like shifting your focus to your own personal experiences for this new book?

Well, I finally did that kicking and screaming. I’m not comfortable in the first person. And I kept questioning why I should tell the story of Syria in the first person. But my editor kept reassuring me that with “memoirs” the narrator can be “I” as in “me me me,” or they can be “I” as in “eye,” if that makes sense. I chose to let my “I” be an “eye.”

From there, I made sure to scrutinize everything the same way I would if it was about other people. I relied on what my journals said I was thinking at age 17, or my letters at other ages, as opposed to how I remember things now. And I was willing to look like an idiot or a fool, rather than be invested in preserving a version of me that was somehow consistent and mature from a young age. And that’s something I learned from my first book, A Country Called Amreeka: U.S. History Retold through Arab-American Lives, and from Patriot Acts. It’s ok if characters are imperfect and flawed, if they transform, change their minds, or make bad decisions. I don’t think readers would recognize characters as real in any other way.

In the early stages of conceiving The Home That Was Our Country, where did you find inspiration? Were there any specific writers or books that were particularly influential for you?

One of my favorite meditations on a place that’s gone through horrible trauma and emerged and is reconciling with memory is Patrice Guzman’s Nostalgia por la Luz, about Chile after Pinochet. I wanted to hit that level of beauty, honesty, and lack of sentimentality.

My friend and mentor Anthony Shadid had a great effect on me. He convinced me I had to be part of whatever story I would eventually write for my book, as he had done in his book House of Stone: A Memoir of Home, Family, and a Lost Middle East. I couldn’t bring myself to read House of Stone for a long time, because the book is about his great-grandfather’s house in Marjayoun, Lebanon, and that house was the last place I saw him before he died. When I finally read it, I just wept. And I felt he had set the standard.

I also read about other societies warped by totalitarianism, like East Germany (Stories from Stasiland); North Korea (Nothing to Envy); South Africa (My Traitor’s Heart); Egypt (The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit); and Libya (In the Country of Men).

Syria and Syrian refugees have had a regular presence in U.S. headlines over the last few years. Why did it feel important for you to tell this particular story as you have, and to tell it now?

I wanted to show Syrians and Syria in their complexity—something Arabs, then Muslims, and now Syrians have been denied. I moved to Damascus with the desire to work on a book in April 2011—I didn’t know then that Syrians would become the phantom menace of the day, used by politicians across Europe and the U.S. to score cynical political points. Now it seems like a necessary corrective, albeit one that I think has come too late given how catastrophic the Syrian situation is now. Now I just hope it means people who read the book mourn with us, for what has been lost. But I’d also like them to be moved to work for a resolution that enables a future for Syria that is viable, free, and safe, for all Syrians.