by Praveena Fernes

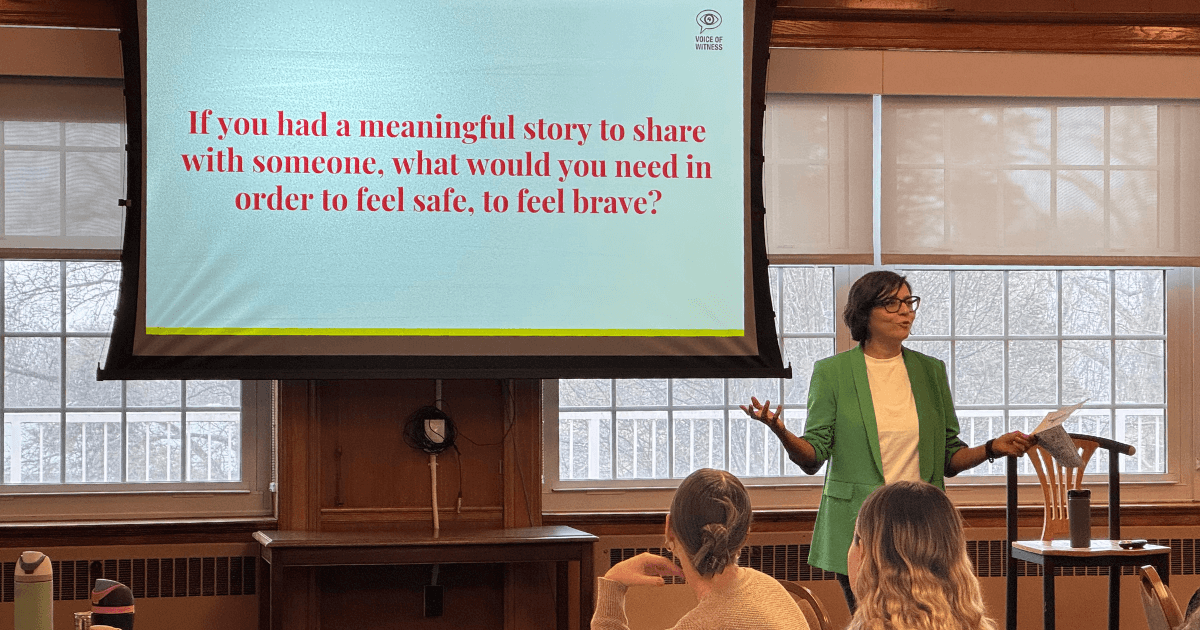

I was 15 when I was first introduced to best practices in storytelling through Voice of Witness (VOW), an organization that illuminates contemporary human rights crises in an oral history book series. Through my seven years of working with VOW, I have learned to use storytelling in my public health work.

Most recently, I completed my year-long Honors Thesis project titled “Storytelling Used as a Public Health Tool” using the Healthy Neighborhood Discovery Tool (DT) and Our Voice Citizen Science for Health Equity (Our Voice) initiative developed by the Healthy Aging Research and Technology Solutions (HARTS) Lab directed by Dr. Abby C. King. The goal of my project was to understand built environment features that help or hinder perceived access to food and healthy living in Orleans Parish, Louisiana using a range of methods that align with my commitment to employing storytelling in health research, including: visual and narrative data, participatory technology, and a geospatial approach.

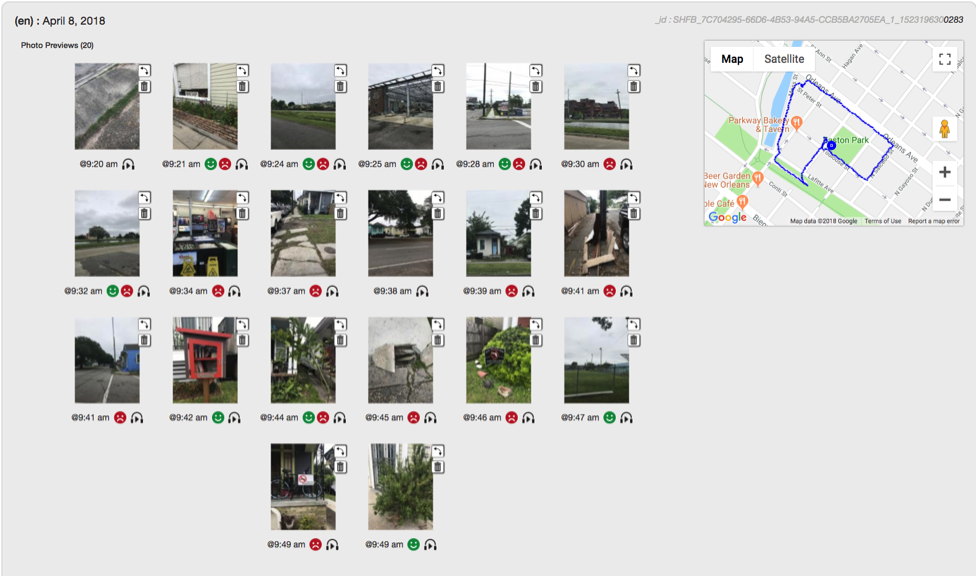

My study was a sub-study of a larger research project directed by Dr. Jylana L. Sheats at Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, and part of the Our Voice initiative. In Our Voice research, citizen science involves ordinary people from communities across the globe who collect and use community data to activate change. Our Voice combines technology and community-based participatory research (CBPR) methods using the DT, which is a mobile app–based environment assessment tool that provides contextual data about neighborhood environment.

Across Our Voice research studies, citizen scientists, or residents in the communities of interest, use the DT to assess features of their neighborhood environment by documenting and sharing insights about their community. For the purpose of this study, citizen scientists were individuals aged 18 years and older who resided in the diverse neighborhoods that make up the greater New Orleans, Louisiana area.

The DT has been adopted seamlessly in diverse low-to-middle income to high-income communities around the world; and proven powerful in building trust between researchers and citizen scientist. Given the unique culture of the city as well as the lasting impact of traumas experienced by New Orlanians (e.g., Hurricane Katrina), this research shed light on key neighborhood elements that have the potential to impact their health behaviors.

There are three general phases in the Our Voice approach:

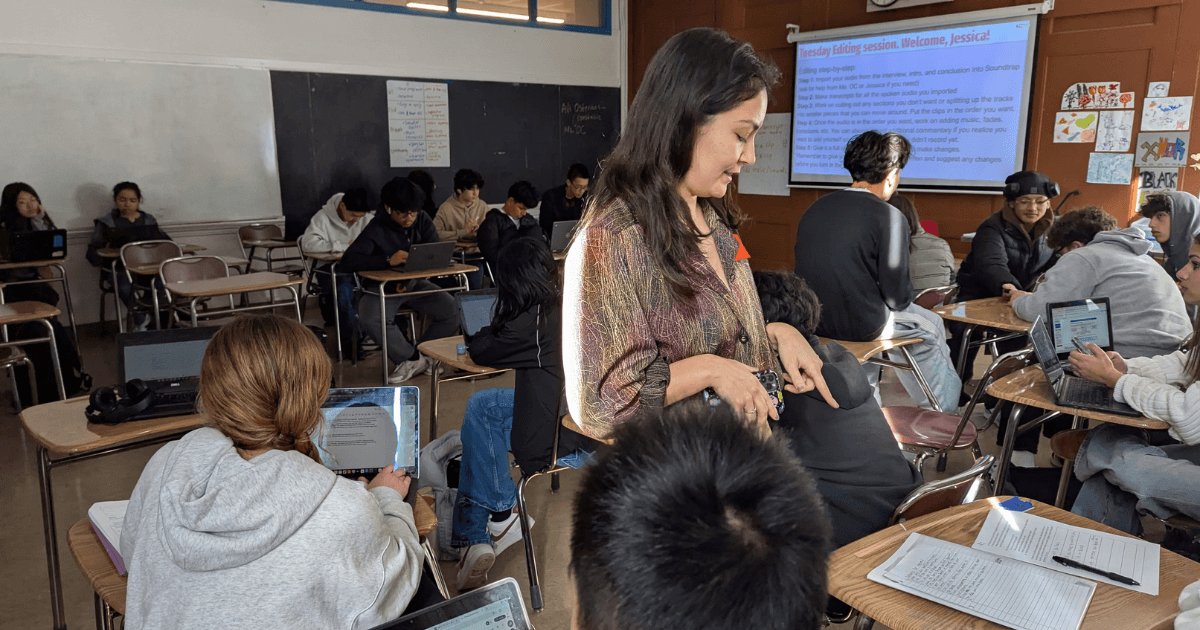

1. Meet with each citizen scientist at their home or a place where they feel comfortable during a predetermined, convenient time of day. Citizen scientists are briefly trained to use the DT and go on a researcher-assisted or solo walk in their neighborhood. While on the walk, citizen scientists use the DT to capture geo-coded photos and audio narratives about neighborhood features that promote or hinder their ability to engage in healthy behaviors. Citizen scientists are then prompted to rate each photo-audio pair as being negative or positive for their community. At the end of the 20-30 minute walk, they take an in-app survey.

2. Citizen scientists review the data (photos, audio transcripts, and ratings), are trained in advocacy skills, and work together to prioritize the most pressing issues.

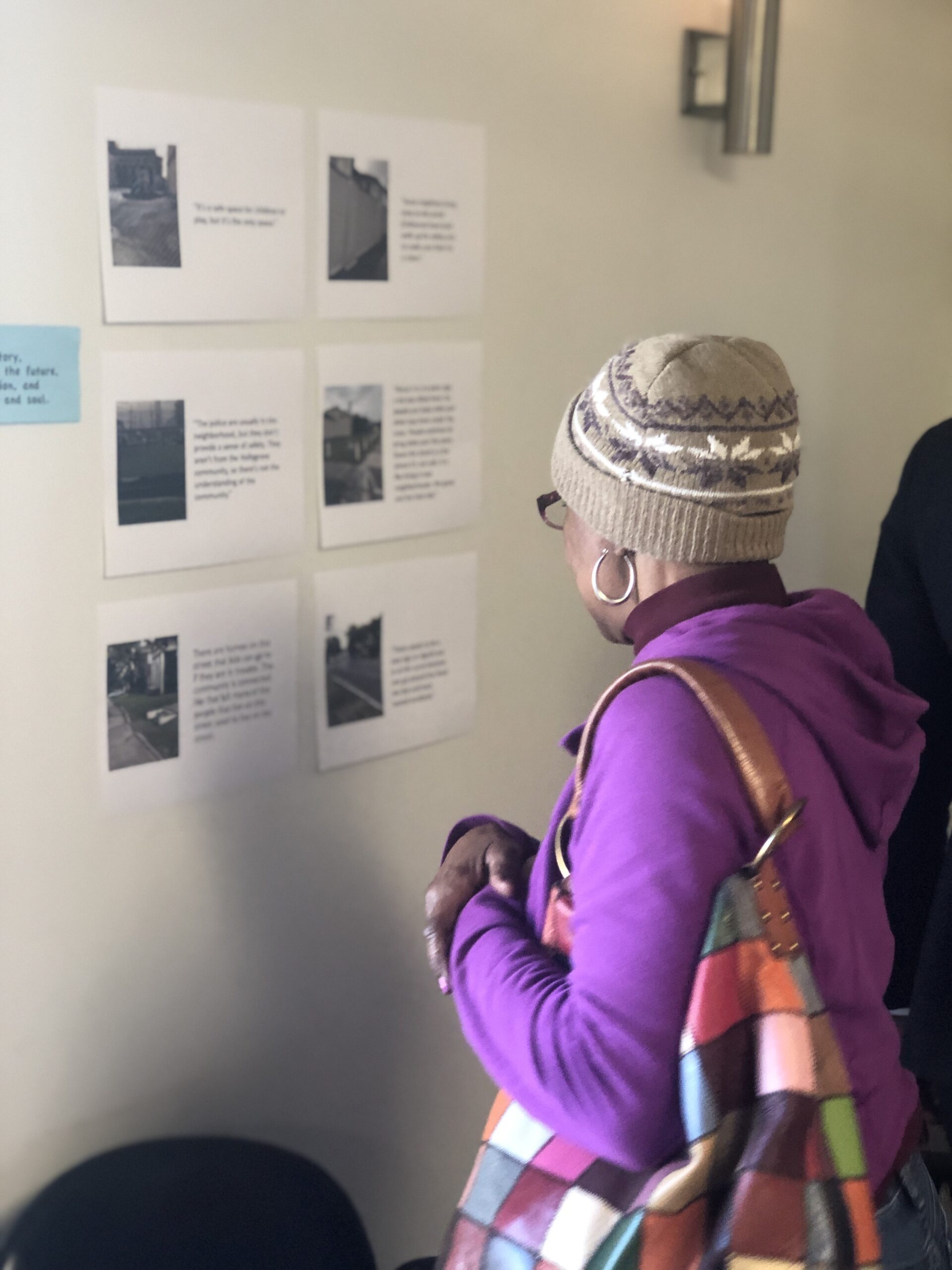

3. Citizen scientists engage in a dialogue with key stakeholders, local decision-makers, and policy makers in a follow-up community meeting to share the Our Voice process, present their data, and discuss solutions for the pressing issues identified by citizen scientists.

While there are three primary phases, they may be modified based on the research question, neighborhood/community, and population. As part of my thesis project, I included a post-walk reflection to obtain greater insights on how this process of storytelling affected them. When asked about their experience, two participants shared the following:

“I wanted to be a voice for my community for the positive and negative things that impact people’s access to resources contributing to their health behaviors.”

“I wanted to share my story because we got an opportunity to walk. Walk the neighborhood. Not just talk it, but walk it! We were able to see some of the areas that definitely need improvement.”

A community meeting was held to share study findings with citizen scientists, other community members and stakeholders representing local organizations as well as the city and state. Not only did citizen scientists share the challenges they experienced in the community (e.g., limited to no access to healthy foods, poor sidewalks or excessive potholes, blight, etc.); but they engaged with other attendees to collaboratively identify solutions and relevant resources.

In conclusion, applying the Our Voice process enabled me to support community members in identifying factors that influence access to healthy living; document their experiences while navigating the local environment; and facilitate a consensus and advocacy-building process to capture, prioritize, and communicate to local decision-makers their most salient concerns and their proposed strategies for changes to promote health and wellbeing.

I leveraged my academic positionality to facilitate engagement between community members and decision makers. This “passing the mic” strategy provides an effective platform for storytelling in which both the storyteller and listener benefit and transform.Praveena K. Fernes, BSPH (May ’18), is an emerging public health professional with five years of broad experiences ranging from analyzing the impacts of government projects and corporate ventures on environmental health in rural Thailand to interning in community health action and policy in a New York kidney care center. She has experience working in chronic disease prevention, gender-based violence prevention, and environmental health and human rights. Currently, Praveena is conducting community-based participatory research using a digital citizen science tool to examine assets and barriers to healthy living in Orleans Parish, LA while completing her degree. She has developed health promotion outreach and training materials, served as a photojournalist focused on rural health disparities in the developing world, and written promotional materials and updates for print and online sources. Praveena spearheaded several successful social ventures, securing funding for the Stronger Than You Think Campaign ($45,000 from Kaiser Permanente to promote healthy relationships), Save The Missing Girls Benefit Concert (raised $5,000+ to establish scholarships for girls in rural India), and Radical Grandma Collective (raised $7,250 to build community center in Northeast Thailand for weaving collective and land rights activists). Each of these experiences have been shaped by her early interactions with Voice of Witness.