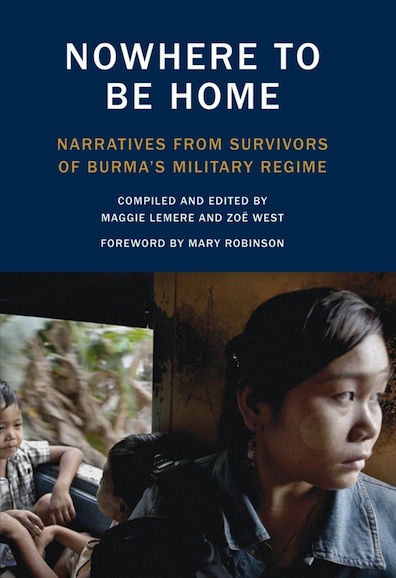

The human rights crisis occurring right now in Burma is nothing new. When we published Nowhere to be Home: Narratives from Survivors of Burma’s Military Regime in 2011, one narrator, Fatima, recounted her experience as a Rohingya refugee living in Bangladesh, and the hardship she faced as a Muslim in Burma.

We must continue to share the stories of the Rohingya and encourage action in Burma. If you are interested in free copies of Nowhere to Be Home (just pay shipping) to learn more about the history and plight of the Rohingya in Burma, visit McSweeney’s and enter the code “VOWShipping” at checkout.

Below is an excerpt from Fatima’s story.

We met Fatima one afternoon in the dense and sprawling Kutupalong makeshift refugee camp, near Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, where she and over 20,000 other stateless Rohingya refugees have made a settlement next door to an official refugee camp. We sat with her inside her mud home, speaking intensely for hours. She kneeled during the five hours of our interview, smiling sweetly and, at times, gently crying while recounting the many trials she experienced in Burma and since her exile in Bangladesh. A dozen or more of Fatima’s neighbors passed by, listening and nodding as Fatima described the fear and daily harassment she encountered as a Muslim woman in Burma.(See footnote 1) Fatima now lives in Bangladesh with her husband. Unregistered as a refugee by the UNHCR, she, along with many of the camp’s inhabitants, are denied official protection and left without sufficient food or other basic resources.(2) Limited employment options, coupled with the risk of arrest and deportation, leave Fatima and her husband with an uncertain future.

WE ARE LIVING IN HELL HERE

We moved to the Kutupalong makeshift camp two or three years ago. We knew how to come to this camp because there were a lot of people gathered here. On the way here, I was crying because we didn’t have shelter.

Initially I raised a shanty on the hill, but the Bangladeshi officials demolished my hut and others’ huts as well.(3) Then I rebuilt again a bit further away, but when they officials found out, they came once again and destroyed the house. The Bangladeshi officials destroyed our hut three times, and each time we just waited. When they went away, we started building again nearby, in a different section of the camp.

The Bangladesh Forestry Department says this is their property, and since this is their property they can destroy our house. When they come, we don’t say anything. We say we don’t have any property, we just have dishes and jars, so we just take these and we go away. The three times that my house was destroyed, I thought, I will go. Because today I make it and tonight they break it. It was really horrible. We couldn’t endure it. Sometimes we felt like committing suicide, thinking, What can we do? Where will we go?

After the third eviction I met a registered refugee who said, “If you want somewhere to stay, there is a place where we plant vegetables and you can stay over there. But you have to pay 200 taka.”(4) Because we live on this land now, the registered refugees cannot plant vegetables here anymore—and if they don’t plant, they can’t earn money. So if we want to stay here, we have to pay them 200 taka.

We paid the money to the registered refugees; we don’t know if they are leaders or not. That’s why I’m here today, and why we made this house here, near the latrine. To make my house, I just collected wood from the forest. I bought the plastic material leftover from rice bags at the market, and then I used it to make the house. Each piece of plastic was 6 taka.(5) We don’t have much money to make our house, and I’m not able to build two shacks. When the rain comes, rain will fall into the house and we have to let the soil dry. We just make a ditch and drain the water out, and then we rebuild our hut again when the sun comes.(6)

The registered refugees look down on us and make some problems for us. They have latrines, but they tell us that we are not allowed to go there. We live near the registered camp, but in order to use the toilets, we need to pay 1/4 kilogram of rice each month.(7) The registered refugees can come to the unregistered camp if they wish, but we cannot use the facilities in the registered camp unless we give them rice. If our little children go to the registered camp and cause any trouble, then the registered adult refugees come to the unregistered camp and beat the adults. If they come here and start to beat us, we don’t tell anyone; we just stay silent because we know we don’t have any protection or identification.

If we go outside of Kutupalong, then other people can catch us and we’ll have nothing. We can’t do anything. We are scared of the Bangladeshi authorities. Even the registered refugees have told the police to break our homes. We are living in hell here—our homes are always broken, we are always starving. But it is still better than living in Burma.

1 According to a 2009 report from Human Rights Watch titled “Perilous Plight: Burma’s Rohingya Take to the Sea”: “The Rohingya are descended from a mix of Arakanese Buddhists, Chittagonian Bengalis, and Arabic sea traders… Centuries of coexistence with Arakanese Buddhists was bifurcated by British colonialism, when the boundaries of India and Burma were demarcated. As a result, the Rohingya became a people caught between states, with the majority situated in newly independent Burma in 1948.”

2 Kutupalong’s makeshift camp population was over 30,000 in early 2010, but according to the Arakan Project it is now reduced to under 30,000.

3 According to MSF (Doctors Without Borders), “The Rohingya population at the Kutupalong camp have been told that they cannot live next to the official refugee camp, supported by the Bangladesh Government and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Nor can they legally live on adjacent Forestry Department land.” Houses were destroyed to create a corridor between the official camp and the makeshift camp.

4 Approximately US$2.85.

5 Approximately US$0.10.

6 For more on conditions in the camps, see page 476 of the appendix.

7 Payment is to offset the costs of cleaning.