The Voice of Witness book series amplifies the stories of people directly impacted by—and fighting against—injustice. We use an oral history methodology that combines ethics-driven practices, journalistic integrity, and an engaging, literary approach.

The books explore issues of inequity and human rights through the lens of personal narrative. Each project aims to disrupt harmful narratives by supporting historically marginalized or silenced communities to tell their own stories in their own words.

Book clubs are useful tools for engaging and interacting with these oral histories and the issues they highlight. Find our handout with guidance on planning and facilitating one here.

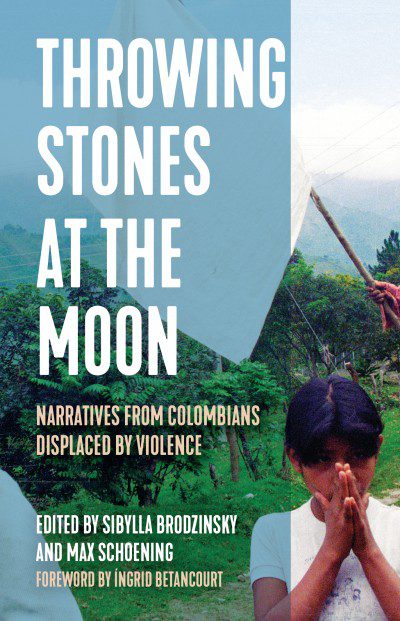

Use the questions below to start a book club for Throwing Stones at the Moon: Narratives From Colombians Displaced by Violence.

Discussion Questions:

- Sergio Díaz and his family suffer personal abuse from actors on both sides of Colombia’s civil conflict, with Sergio losing his leg to a FARC landmine and government Marines frequently harassing the Díaz family on their property. What does Sergio’s narrative reveal about the position of Colombia’s rural poor in the conflict between the government and guerrilla forces that claim to represent rural interests?

- Two years after paramilitaries inflict a massacre upon El Salado, Bolívar, Emilia González returns to her home and makes it her mission to unify residents in fixing up the long abandoned village. In her words, “We shouldn’t have to have some government agency or NGO come clean the village—we ourselves have to clean our town, especially the cemetery. The cemetery is an embarrassment.” Why do you think Emilia has this perspective? Do you agree or disagree with her convictions about how the village should be restored?

- Referring to the government aid she and her husband receive after fleeing La Alemania, Julia Torres states, “I wasn’t born to ask for hand-outs, to go begging for things, or to have people pity me. That’s something that’s very hard for me. It’s not my style.” What does this statement tell us about the intangible effects of displacement on a person’s psyche and emotional well-being? What are psychic and emotional consequences of displacement that other narrators mention?

- Amado Villafaña has never registered as displaced person; due to spiritual beliefs, he remains a member of the indigenous Arhuaco people. “Spiritually,” Amado explains, “things need to be repaired and replaced. So we don’t see [displacement] as just someone else’s fault. We too are responsible.” What is your response to Amado’s interpretation of his experience as a displaced person? How does his view complicate your own thinking about displacement?

- Lina Gamarra is traumatized by Social Action’s disparaging her deceased husband’s memory when the agency refuses to pay reparation for his murder. Lina declares, “the memory of my husband has to be pure, like he was. I won’t rest until his memory is restored.” What role do you think memory plays in Colombia’s decades-old civil conflict? How is memory shaped, manipulated, and devalued by powerful actors and the structural injustices that manifest during conflict?

- As a child, Carmen Rodríguez was traumatized by witnessing how the Colombian army handled the bodies of two guerrilla leaders they killed, the Vásquez Castaño brothers. What evidence do Carmen’s reflections offer as to why conflict between Colombian military and rebel groups has been so irreconcilable?

- Zullybeth poses concerns for the futures of her daughter and speaks about how they have been affected by forced displacement, noting how they have become more aggressive with one another and that their performance and behavior in school have declined. What specifically about their displacement influenced these behavioral shifts? Where else do we see such intense, negative behavioral changes manifest within other narratives?

- Alfredo and Ricardo’s narratives end in a very similar way, with each man speaking on how, in times of exhaustion and creeping despondency, he remembers his children and splashes water on his face in order to persevere. What do these descriptions tell us about the longterm, physical effects that forced displacement inflicts on the body?

- Reflecting on the many traumas of her life, Mónica Quiñones says, “Sometimes I feel as if I were living a borrowed life. Half of Mónica remains, because the other half is already dead … When you live like this, you live like the dead.” What do you think Mónica means by “living a borrowed life”? How does reading Mónica’s perspective help us better understand both her situation and the situations of other displaced persons in Colombia?

- Throughout his narrative, Jesús Cabrales focuses on the importance of principles and a commitment to positive values. He states, “A person’s values are what he’s worth. If you don’t have values, you have nothing; you don’t have dreams. And your dreams are your

reality, because your dreams make you who you are. If you don’t have dreams and can be won over easily, your principles end.” What are some of the principles that guide Jesús, and what dreams do you think he has for his own future and the future of his country? What sort of values must Colombia’s leaders adopt in order to address the dreams of everyday citizens?