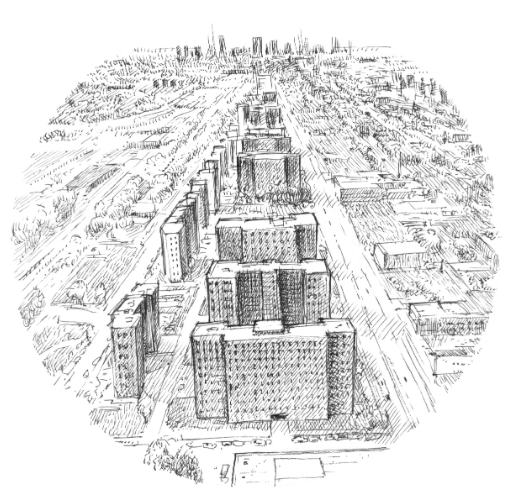

We’re proud of the diversity of Black voices around the country featured in our oral history book series. From places like Chicago to New Orleans, these first-person narratives challenge stereotypes and misrepresentations of Black history and culture that are all too pervasive in mainstream media.

To celebrate Black history today and everyday, here is a glimpse into the lives of five Black American narrators from our books High Rise Stories: Voices from Chicago Public Housing, and Voices from the Storm: The People of New Orleans on Hurricane Katrina and its Aftermath.

Yusufu Mosely, Narrator in High Rise Stories

Didn’t Many People Know About Black History

Most of us didn’t grow up understanding who we were or where we’d come from. Didn’t many people know about black history. We didn’t know about Langston Hughes or other great thinkers. There was Negro History Week: an upgrade from Negro History Day. We learned a little about Booker T. Washington and George Washington Carver. But we didn’t learn much. We just thought of Carver as the peanut man. He was a genius. Little did I know this man had a skill for nature. I’m glad to have that fuller picture of him now, but it was good to have some exposure like that because we could imagine that our history was more than just slavery.

Dawn Knight, Narrator in High Rise Stories

You Grow Up With That Fear

When I was a small child, we used to live in an apartment on Sixty-Eighth and Wood in Englewood, and over there, white people would march through the blocks picketing for us to move. The march I most clearly remember was in 1976. They didn’t want black people in their neighborhood. They didn’t want us to move past Cermak or Western Avenue—I guess that’s where Marquette Park started. We couldn’t cross Marquette Park. We couldn’t cross Western. We knew that. How far black folks lived over there, I don’t know, but we knew Do not cross Western. Do not even go near Western. You’ll get hurt over there. That was something our parents told me and my siblings. The white people marched down past where we lived, and we four kids would just run in the house. I had a mental image that they were going to lynch us. They would have bull-horns and signs, and the only thing I knew about white people is that they hated us, you know, we were slaves and they lynched us. So you grow up with that fear.

Dolores Wilson, Narrator in High Rise Stories

They Made Me Move Too Fast to Hold On To My Mementos

Everybody was moving in all directions. The housing office kind of steered you to where they wanted you to go. I’d been interested in Hilliard homes and Parkside, but they said those places weren’t taking applications. Quite a few of us headed to the Dearborn homes, where I live now. My daughter’s right nearby. But we’re not all in the same building. The people I’ve known from Cabrini are all in different buildings. And when we see each other, it’s “Ohhh ahh!” like we haven’t seen each other for a thousand years. And a lot of them, their sons come to visit, “How you doing, Ms. Wilson?” ’Cause I’m there by myself. “Are you all right? You being taken care of okay?” And they come back and keep checking. “You want anything from the store?” All times of day and night they stopping in, I can hardly rest, but I get up anyway and say, “Thank you for coming.” Young guys, their mommas probably send ’em to ask me. That’s the way it’s supposed to be. That’s family. That’s what it is.

Jackie Harris, Narrator in Voices from the Storm

Looking Back

Music in New Orleans is not just entertainment or a hobby. It’s a way of life. Young people in New Orleans are exposed to music in the womb. You look at young parents attending concerts, you look at parents participating in second-line parades, you look at kids listening to music at an early age, kids playing music in the streets at eight, nine, and ten years old. You know music in New Orleans is a necessity. We need music in New Orleans as bad as we need water and food. I can’t spend more than a day or two of not hearing some music, some New Orleans music.

New Orleans music will make you just want to jump up. When I hear that music, man, I wanna move. Even if you don’t jump up and dance, you pat your feet, you’re bobbin’ your head, you’re clapping your hands. You’re thinking about joy. That’s what it is. It’s a release. It’s an expression. I mean, we use this music to celebrate life. We use it to celebrate death. We use it to celebrate good times, bad times, football games, parties, mourning situations. I mean, it’s a necessity of life for us. Is it because of our human experience? Maybe it’s because we’re totally surrounded by water and we live very close to the land. Maybe it’s because we’re a gumbo of all of these cultural offerings. Maybe it’s because the African-American experience has been an experience of oppression.

Patricia Thompson, Narrator in Voices from the Storm

Looking Back

Katrina made me aware that racism is alive and well. I have been taught to undo racism, but Katrina only was the proof in the pudding that racism is alive and well. Eighty percent of New Orleans rides public transportation. That lets you know that these people don’t have cars. I lived there, but I’m sure the mayor, the governor, and the president knows it as well. First of all, we shouldn’t have got a mandatory evacuation order less than twenty-four hours before the storm made landfall. The meteorologist and everybody was saying how bad that storm was going to be. Preparations should have been made to get us out of there.

That’s what let me know that the race card was being played. Because when just about everybody that could get out had gotten out, the city was primarily black. They tried to keep us there. They were waiting for a few more of us to die. I will die believing that and I’m not telling you something anybody told me. I lived maybe five or six blocks from a very well-to-do neighborhood. I’m in the ghetto, but five or six blocks down it’s a very prestigious white neighborhood, St. Charles. There wasn’t a drop of water in St. Charles.