2019 marks 10 years for Voice of Witness as a nonprofit, and in celebration of this exciting milestone, we’re resurfacing powerful stories from every oral history book in our series. Though time has passed since these stories were first published, many of the themes and issues they address are as relevant and important as ever.

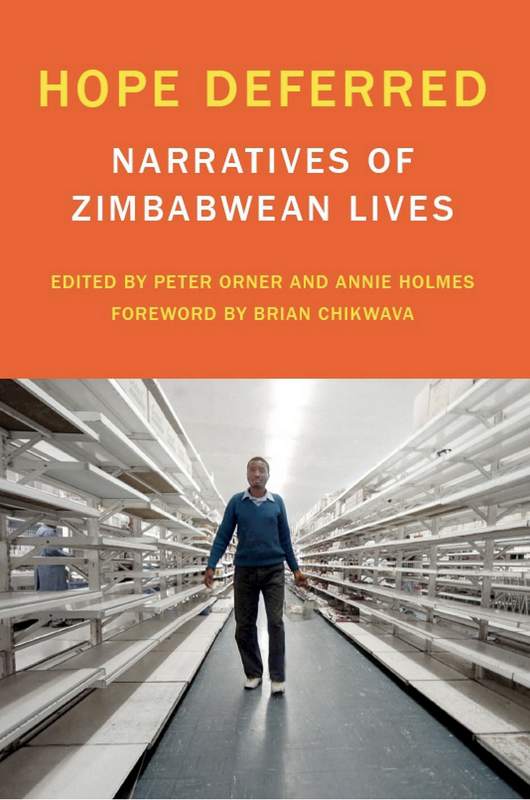

Nine years ago, we published Hope Deferred: Narratives of Zimbabwean Lives, which illuminates one of the worst humanitarian emergencies of our time.

Nine years ago, we published Hope Deferred: Narratives of Zimbabwean Lives, which illuminates one of the worst humanitarian emergencies of our time.

This book asks the question: How did a country with so much promise—a stellar education system, a growing middle class, a sophisticated economic infrastructure, a liberal constitution, an independent judiciary, and many of the trappings of Western democracy—go so wrong?

In their own words, Zimbabweans recount their experiences of losing their homes, land, livelihoods, and families as a direct result of political violence. They describe being tortured in detention, firebombed at work, or beaten up or raped to “punish” votes for the opposition. Those forced to flee to neighboring countries recount their escapes: cutting through fences, swimming across crocodile-infested rivers, and entrusting themselves to human smugglers.

This book includes Zimbabweans of every age, class, and political conviction, from farm laborers to academics, doctors to artists, opposition leaders to ordinary Zimbabweans; men and women simply trying to survive as a once-thriving nation heads for collapse. Order your copy of Hope Deferred here at 50% off!JOHN NDHLOVU’S STORY

Even though John Ndhlovu had successful careers in Zimbabwe as a teacher, editor, and journalist, it is clear when he talks that his passion has always been politics. John’s story takes us further back in time, and provides an insider’s account of Zimbabwe’s independence and the pivotal events of the early 1980s. He started working for the Zimbabwe African People’s Union, Zapu, when he was in college, organizing meetings and recruiting guerillas to fight at the front, and when the war ended, he managed publicity for the elections.

A man who has found himself on the wrong side of two successive regimes, John was harassed by police and agents from Ian Smith’s government during the liberation war, and then arrested and imprisoned thirteen years later by Robert Mugabe’s regime. When asked why he’d been put in prison the second time, he laughed and said, I married the wrong woman. The woman was Zapu president Joshua Nkomo’s daughter.

In 1983, two months after his wedding, John was arrested for helping Nkomo flee the country. John was in prison for a year, and after his release moved with his wife and young son to Vancouver, BC.

John laughs easily. He laughs about the mysterious accidents that have killed his colleagues, about his treatment during interrogation, a laughter weighted with many other emotions. This is ever so funny, he says at one point. Then he opens his shirt to reveal a network of scars, like worm trails in wood, across his chest. Cigarette burns, he says, this time only half-laughing.  I WAS TOO HOT A POTATO TO GET INVOLVED

I WAS TOO HOT A POTATO TO GET INVOLVED

I was released in September of 1983, and then I spent a few weeks in Zimbabwe. Then my wife and I spent a month in Dakar. I had been beaten up so much in prison, and I wanted to get checked out at the U.S. Embassy clinic in Dakar. I also wanted to see my mother and father.

After Dakar, we flew to New York. We needed fresh air. We stayed for about a month with Arthur and Mathilda Krim, who had looked after Thandi while she was in school. Arthur owned Orion Pictures and his wife was one of the scientists who had identified the AIDS virus in the early ’80s. We stayed with them in their place on East 69th. They told us that the bedroom we were using was once used by John F. Kennedy!

After that, I went and spent another month in Birmingham, Alabama, with a cousin of mine who’s a doctor there. We came back to New York from Alabama the Monday after Thanksgiving. We spent the rest of November in New York, I think, then went back home to Zimbabwe for Christmas.

I didn’t have to work at that time, but there was a shortage of science teachers, and a man I had gone to university with was headmaster of a secondary school. He asked me to come and teach high school biology, so I went back to teaching for half of ’84 and part of ’85.

I wasn’t involved in politics anymore. I didn’t want to be. I was clandestine. I was too hot a potato to get involved, even though I still had contacts with my journalist friends. I would put them together with people who came out of the countryside where the people were being killed during Gukurahundi.

“It was a big intimidation campaign. Things were getting bad again.”

The ’85 election was approaching, and things were hot. It was the first election after Independence. Nkomo had come back in ’83, just after I was released from detention, and he entered the election. But he was muted. Zanu had started deploying their troops again in the countryside and forcing people to vote for Zanu and not for anyone else. It was a big intimidation campaign. Things were getting bad again.By that time there were tens of thousands of people killed, mostly civilians, always with the excuse of looking for dissidents. But there was no insurrection or organized rebellion—even though the Zimbabwe News kept reporting that there was.

I tried to fly out on British Airways. My wife and I were supposed to leave separately. And so I drove to Harare, got on the plane—and when the plane was about to leave, these state agents came in and demanded that I get off the plane. I was reluctant to go, and the captain said, You stay there, I’ll take you to London. And if they want to come along, they can come for a free ride.

Then I thought, If I go, my wife and child won’t be able to leave. There would have been trouble for them. So I got off the plane and they took me to the police station and interviewed me. I was at the police station until about three in the morning, and then I drove back to Bulawayo. They had asked me to come back to the police station in the morning. Instead, I drove back home.

For two weeks, there was a lot of negotiation over our fate. It went all the way to Mugabe himself. My father was, by that time, back home. He had just retired from the diplomatic service. He phoned Mugabe and Joshua phoned Mugabe, too, and they negotiated and asked him to let us leave, as we were no longer part of his fight with Nkomo. Finally Mugabe agreed to let us go. I left two weeks later with my wife and child, who was a small baby then. He had just started crawling. He was born in August and we left in May.

We decided to come here, to Vancouver. My brother-in-law had left Zimbabwe earlier and had settled here. Canada was willing to take refugees from Zimbabwe. And Vancouver had a good climate. It’s not as cold as Toronto and Montreal. In Zimbabwe it’s dry sunshine, here we get wet sunshine.