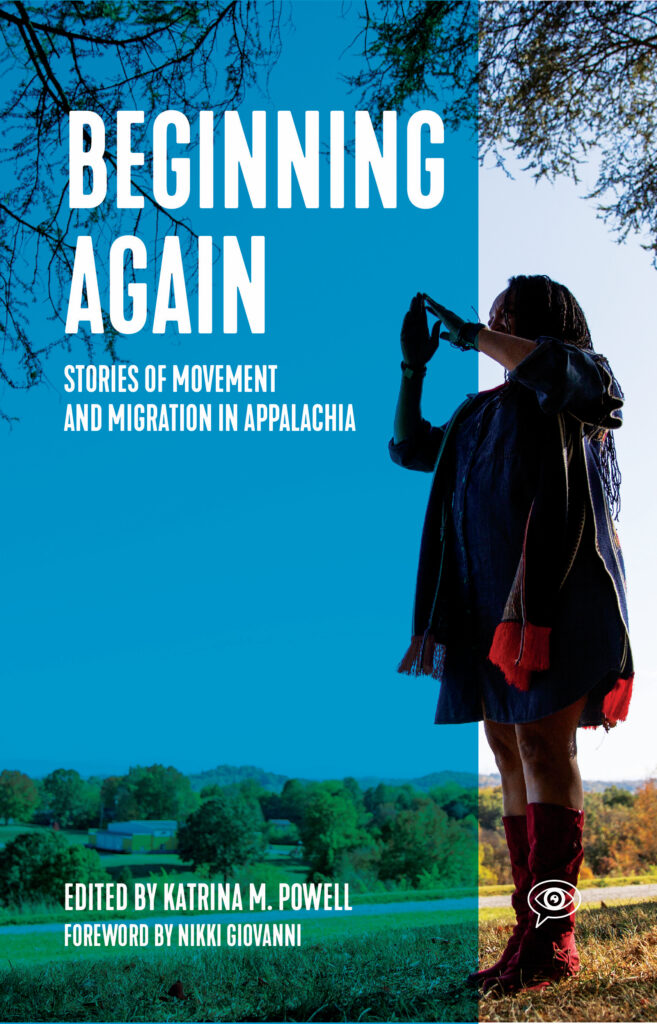

Beginning Again: Stories of Movement and Migration in Appalachia is the next book in the Voice of Witness Book Series, scheduled for publication in June 2024.

In this collection, twelve narrators share accounts of their experiences (or their families’) of migrating and relocating to and within Appalachia. These first-person stories of displacement, trauma, and community integration in Appalachia are complex, and the book counters monolithic representations of rural Appalachia as a region of poverty and strife. With a focus on shared resettlement experiences, Beginning Again presents an expansive and sober look at life in contemporary Appalachia.

At the end of last year, VOW sat down in conversation with project editor Katrina “Katy” Powell and narrators Elvir Berbic and Claudine Katete to discuss the book and the power of sharing one’s story.

- Elvir Berbic is from Derventa, Bosnia, and came to Roanoke, Virginia with his family when he was fourteen years old in 1995, after living for three years in refugee camps in Croatia. A student affairs professional in higher education for the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, he also volunteers with teenage boys through a local soccer enrichment program.

- Claudine Katete spent most of her life in the Osire Refugee Camp in Namibia. Her family fled Rwanda in 1994 when she was two years old. She came to Roanoke, Virginia, when she was twenty years old in January 2014. Claudine received a degree in social work from Mary Baldwin College in 2020.

- Katrina Powell is a professor of rhetoric and writing and director of the Center for Refugee, Migrant, and Displacement Studies at Virginia Tech. Author of The Anguish of Displacement: The Politics of Literacy in the Letters of Mountain Families in Shenandoah National Park, her research focuses on narratives of displacement, human rights rhetorics, and social justice.

Read the Q&A below:

VOW: Can you share a little bit about the history of resettlement in the region and what made you want to explore this topic using oral history?

Katy: I grew up in Appalachia myself, in a rural town in the Blue Ridge Mountains in Virginia. My dad’s side of the family has been in Appalachia for generations, migrating from the Scottish Highlands in the mid-nineteenth century. When I was growing up, we hiked nearly every weekend in Shenandoah National Park, and I was always aware of the history of displacement and resettlement in and around that land. So my whole life, I’ve lived in a diverse community where movement, mobility, and forced displacement were routinized and historical. In 2017, the Trump administration enacted a travel ban on Muslim countries, using racist and damaging stereotypes about refugees and migrants. As in many other communities in the United States, refugees and migrants were resettling in Appalachia from Syria, several countries in Africa, Central America, and other places all over the world. This wasn’t a new phenomenon, but the media portrayal of the situation as a new crisis, then, in turn, placed blame on individual families and perpetuated stereotypes of refugees and migrants as victims or a drain on resources. I knew from living here, from teaching Appalachian students, from researching displacement narratives, and from being a neighbor, that all those negative stereotypes not only were not true, but they were damaging. They influenced policymakers as resources were being distributed, and they precipitated many human and civil rights violations. So I proposed the project to Voice of Witness because I wanted to place the diversity of narratives within Appalachia from families whose ancestors have lived here and from families who had just arrived. Placing those things together to highlight the region’s diversity and the long history of movement, migration, and resettlement.

VOW: Claudine and Elvir, you both play a crucial role in this project as narrators. Could you tell us a little bit about what it was like to share your personal stories and what inspired you to do so?

Claudine: What inspired me to share my story is—well, I talk about my story pretty much all the time. When I meet somebody who is interested in knowing where I come from, I’m always excited about it. For me, it’s kind of a way of coping because I don’t know my country. I was born in Rwanda. I don’t remember, I have zero memory. So my whole life felt just make-believe. When somebody is interested and wants to know my story, I want to share it with them. There are a lot of people who don’t get a chance to have a primary conversation with somebody who was a refugee, so it excites me. I want people to know about my story so that they can learn from it.

Elvir: I think talking about one’s experience, and particularly an experience that highlights the individual within the grand scheme of things, is very necessary. We tend to learn a lot from reading news or excerpts from TV or even the movies. So telling an individual’s story, a truth, that is from the perspective of somebody who lived it is very important. Like Claudine, I find that there’s a therapeutic way of telling your story. A lot of our history, and specifically in Bosnia, was lost due to the war. Things were burned and destroyed, and they’re no longer there as something you could hold on to. So the story goes from one generation to another generation all through oral methods. I think that is very necessary to keep going, even if it’s on this other continent.

VOW: One of the things that defines the work that we do at Voice of Witness is the way we approach every project with a sense of discovery and a willingness to be surprised, to have our assumptions and biases challenged. Has anything surprised you about participating in this project? Who do you want to read these stories, and what would you like them to learn?

Elvir: I feel like the stories should be read by individuals who are trying to sift through information that is too wide of a lens. When you’re reading the news, you’re reading about experiences that are too broad. Within this bombardment of all this news, the individual stories are what make a difference. I mean, my wish in this whole world, is to not have refugees, for people to not have to leave their own homes, because nobody, I can tell you, nobody wants to leave their own home. Well, both of our stories, Claudine and I, are very much positive stories in a way, in terms of how we made our lives better through hard work and a little bit of luck and good health. Behind all of those stories is how we didn’t really want to leave our homes, that we could have impacted our own countries and our towns and cities.

Claudine: The only thing I know about my country is from reading the news or from the magazine or from my mom telling the stories of how we lived. I’m now American naturalized, I’ll have children with that possibility. But I don’t want to forget that history, I want to pass it on to my kids so that they know. But I have the experience of growing up in a refugee camp, I used to think that was my country in fact. You know, like my mom was like, no, you have an actual country, you have an origin we came from.

So it’s really special when I get an opportunity to share that part of my life. It makes me feel fulfilled because somebody else knows and is informed about my story. I have met people who will ask me what a refugee looks like. Like here in the US. And I’m like, Whoa, what? It blows my mind and is very surprising because they have no idea. Like, anyone could be a refugee.

VOW: What was the most reassuring thing about being part of this project?

Elvir: I think the most significant part to me is just telling the story. I’m alive to tell it. The reassurance that I’m okay. You know, I am. I realize that as I am telling it, in this sort of therapeutic way, I am okay with doing this. I have control over it. I am telling this story, I’m no longer a victim in it. I am not an antagonist or protagonist. I am just a truth-teller.

Claudine: I know that that is my experience. Maybe somebody else, like a young person, will read it and relate to it, “Claudine actually went through a similar situation to me. I feel I can also do it.” It is reassuring that it could maybe encourage somebody to do something positive for themselves.