Eddie Leman’s Story

At the time of his interview for High Rise Stories, Eddie was enrolled in graduate courses in business administration at Chicago State University. He maintained a busy schedule, studying, coparenting, working at the Hines Veteran’s Hospital, and developing his own brand of granola mix. Over the course of many conversations, Eddie shared personal photographs, newspaper clippings, and inspirational quotations, from Ann Landers to Buckminster Fuller. A self-described chameleon, Eddie attributes his flexibility and fortitude to lessons learned during his childhood in Robert Taylor Homes. He speaks of the fourteen years he lived there (1968–1982) with a mixture of affection, wonder, and regret—Robert Taylor Homes was where he enjoyed connection with an extended network of family.

I heard stories when I was a child, from my uncles and people that lived there, that the Robert Taylors were built as a housing project very strategically. If there ever was an uprising or something: easy access for tanks to come down the Dan Ryan and target the buildings. Or motorized military vehicles. And I thought about that even as an adult. Mostly all the projects are next to expressways in Chicago. Easy access for military vehicles.

They built the police station over on Forty-Third Street, but this was years after the Robert Taylors were built. They built the station in the late ’90s or something. Before that, I think the closest station was so far away—Fifty-First Street, over on Halsted. Well, there were so many buildings at Robert Taylors and sometimes the numbers were torn off the building, so if you called the police and told them, “I’m in 4429,” they probably wouldn’t even know which building that was, and so that might have contributed to the police not coming when residents called in emergencies. And another thing: if you tell them what you’re on, it’s sixteen floors in the building, you know? If the elevators ain’t working, then nothing’s moving, including the police. They’re not about to walk up all those stairs.

Even when the elevators were working, the lights were out half the time. They used to call them death traps. People got their arms or their body caught up in there.

EDdie Leman

Narrator

Even when the elevators were working, the lights were out half the time. They used to call them death traps. People got their arms or their body caught up in there. The elevator closed tight, like a clamp. You’d have to hold it with both hands and try to open the door if it was shutting.

There was no safety sensor. People were routinely stuck, hurt, trapped in there. They had one red button bell in there to ring, but that didn’t do anything. The only way to open the elevator safely was to use this long six-inch key. It was like a stick and you’d open the elevator with that, but those keys weren’t never around, so you’d have to pry yourself out. And when you climb out, you’ve got to jump down or climb up. You’d be stuck between floors. You get on the elevator, you risk getting stuck, you risk getting hurt, you risk getting robbed. That was every day, all the time. and I lived on the fifteenth floor, so you know I had my exercise on.

When I was growing up, I never saw ambulances. There was so much crime around there, maybe they didn’t come because of their safety. In Robert Taylor, they had little chain-link fences along the parking lot held by metal beams. And these metal beams had sharp edges. When I was a little child, eight or nine, I was sitting on one of the metal beams and I got up to play. The metal beam ripped my leg open. We waited for the ambulance, but it never came. So my mother got a ride and we rode to Provident Hospital.

Provident was just a tragedy. I remember seeing roaches, bloody tissues, everything. Ten stitches I needed for this cut. It was about two inches deep, two inches wide. Because it was unsanitary in the hospital, the cut got infected and it didn’t heal right. And when they stitched it, they didn’t stitch it closed. They had it wide open. Ten stitches. The scar is about three inches long. Big as a finger. The stitches are about half-an-inch apart. Looks like a centipede. It’s disfigurement. And I got to carry this all my life.

Read Eddie’s full oral history in High Rise Stories.

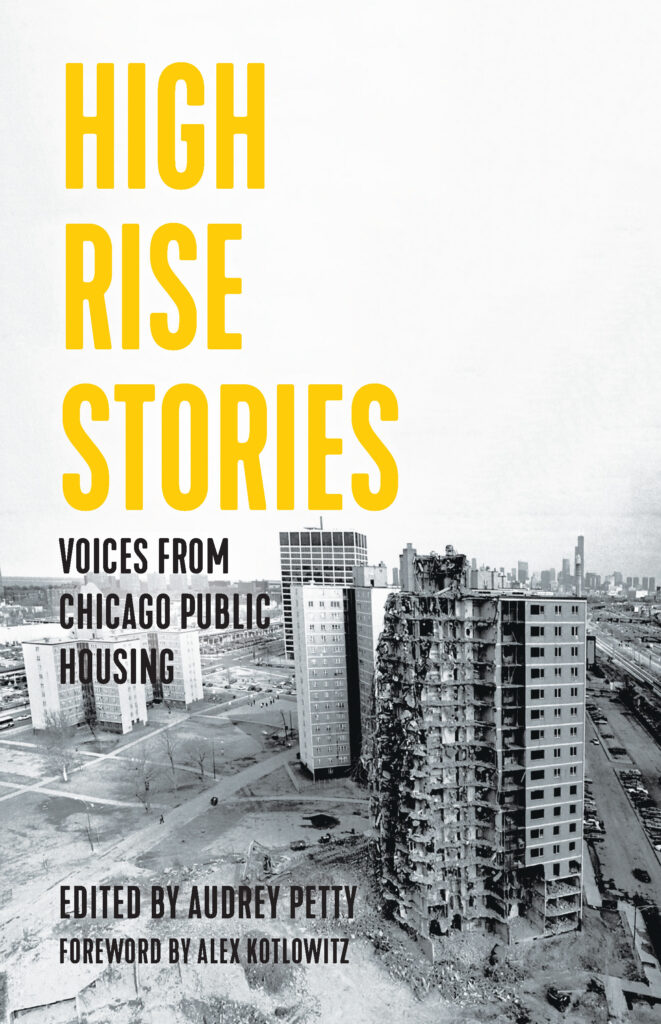

High Rise Stories: Voices from Chicago Public Housing

Edited by Audrey Petty

High Rise Stories follows the lives of 12 former residents of Chicago’s iconic public housing units. In 2003, the destruction of the 28 buildings that comprised Robert Taylor Homes was aired widely on the news and YouTube. But the stories of the people who lived in those buildings – the families and communities – and how the demolitions impacted them are largely unheard.

High Rise Stories’ first-person accounts of community, displacement, and survival in the wake of gentrification amplify the voices of many who have long been ignored, but whose hopes and struggles exist firmly at the heart of our national identity. This book reveals how residents made their homes, and how, in the face of (and in spite of) direct and structural violence, they resisted, connected, and survived.

More From the VOW Book Series

The Voice of Witness oral history book series amplifies the voices of people directly impacted by—and fighting against—injustice. We use an ethics-driven methodology that combines journalistic integrity and an engaging, literary approach to oral history. The books explore issues of inequity and human rights through the lens of first-person narrative.